A compilation of quotes and transcriptions from all available sources.

June 15, 2023

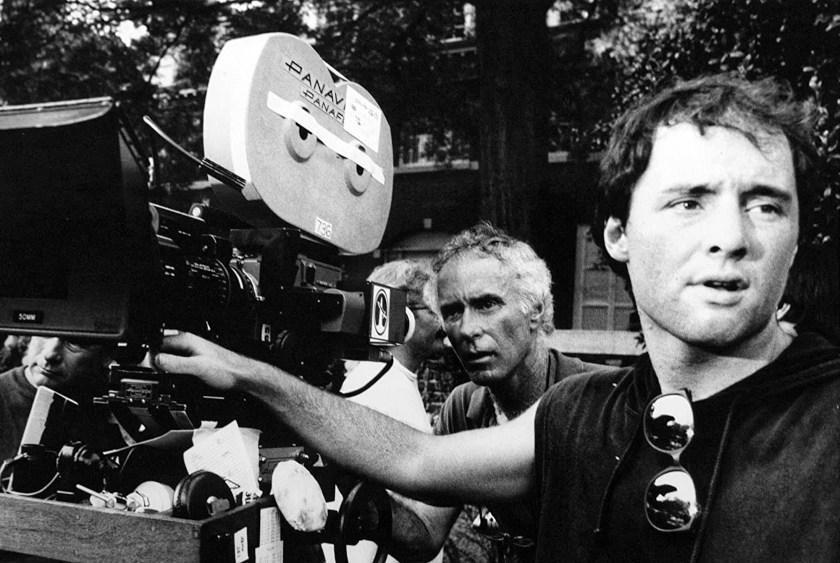

As part of the 2023 Tribeca Festival “Directors Series” live conversations, David Fincher discussed his career, filmmaking process, and philosophy with his fellow director and longtime friend Steven Soderbergh, before an audience in the Indeed Theater at Spring Studios in New York.

Fincher and Soderbergh first met 32 years ago, just after Fincher had been fired for the second time from the troubled production of his first film, Alien3 (he was later fired once more):

I came out of a truly fucked-up situation and kind of swore that I would never make the same mistake. I made a lot of brand-new ones, but I’d never start something that didn’t have a script that I didn’t believe in or that I didn’t understand or that I couldn’t articulate to people. And I’d also very much learned that I wanted to make all my own mistakes instead of inheriting them from other people.

The two explained that they have been talking about twice a week for the past 20 years, and that they regularly show each other rough cuts of their works in progress for feedback.

Soderbergh: I think the next time we saw each other, I was doing an episode of Fallen Angels [in 1994], the second season of a noir series that was on Showtime. You were going to do one. And I saw you in the office one day. And then you weren’t able to do one because you Seven got greenlit. And you went and did that thing.

Fincher: Yeah, it was one of those. It was a strangely rushed pre-production on that. Michael De Luca basically said, ‘if you can be up and making this movie in six weeks, we’ll greenlight it.’ So that was one of those, ‘okay, let me shut down the rest of my life.’

Fincher revealed how he approached shooting Music Videos as his film school:

I really went at it going, ‘I don’t want to spend my own money trying all this stuff out, so let’s see if Madonna will finance it.’

Soderbergh: You’re one of the few people who came out of the 80’s whose visual sense was matched by the importance of performance, and the understanding of a two-hour movie narrative… a lot different than a commercial or music video.

On The Social Network:

It was a pretty tight script. And part of getting it made was saying, ‘we’re gonna get this in under two hours, even if it’s 178 pages or whatever it is, we’re just gonna have everybody talk really fast.’

Fincher has learned over the years that it’s best to first discuss every aspect of film production with the cast and crew.

When I was younger, when an actor pushed back at me it felt like they were calling out the quality of my interpretation. I don’t feel that way anymore. It’s fun to get into that dialogue. It’s fun to find different avenues to explain how you see something evolving.

There’s no such thing as my editor, or my cameraman. It’s the people we’re lucky enough to get. And if you really do feel that you’re lucky enough to get the costume designer that you want, it’s incumbent upon you to squeeze them for everything that they have. It’s more on you to get their best. Because it is Darwinism. The best ideas not only will win out, they should win out, and everybody’s there to help you.

Soderbergh asked Fincher to break down a montage in Fight Club which, by Soderbergh’s estimate, involved 75 to 80 shots. Although the montage created the illusion that the Narrator played by Edward Norton was traveling across the country, everything was actually filmed within five or six blocks of LAX:

I really love a good montage. I love the montage because it’s pure cinema, it’s inference. It’s like, this goes against this, as quickly as we can possibly make a point and get the fuck out of Dodge. Then the question is where do people’s eyes need to be.

Soderbergh observed that Fincher seems happiest while imagining a project versus actually being in production, and felt that he’s seen the movies Fincher didn’t even make because of the way he has laid them out in his office.

I have enough of a reputation as a misanthrope that I don’t need to feed into that.

Shooting for me is a lot of indigestion and reality. They just keep seeping into everything you’re trying to do. So that part of it is difficult. And I think the first couple of times I had stuff fall apart even for the right reasons.

Asked by Soderbergh what he considers the “fun part” of filmmaking:

I love rehearsal. I love talking to people about the intention. I love haggling over every single word, and what the script means, and listening to people read it, and hearing their ideas. I love casting, I love the casting process. I love designing the movie. I love sitting with the production designer, and the director of photography, and all the art directors. And talking about what do we want to say, and where do we want people’s attention, and what are the things that we have to underline.

By the time it gets to the shooting… I don’t enjoy shooting. I find it to be unnecessary. I would much rather love to just workshop it, and then have someone else take it over, after all those conversations, and bring it home. But you got to be there.

I remember debating Francis Coppola and the Silverfish. And the idea of working over with a microphone over a P.A. system ‘okay, pan A camera left.’ And I don’t think you can… I think movies require you to impress upon people the amount that you’re sweating it, the amount that you care. They have to see it in your face. They have to see it in your eyes.

There was a really interesting thing last year, shooting a movie [The Killer] with all of the COVID protocols, working through a mask and a visor. I had no idea how much I was imparting with making faces and sound effects. It was a completely different experience.

On the stress of directing:

Directing is storytelling through a medium that requires an awful lot of personnel to just support what you’re doing technically and what you’re doing just from a logistical standpoint. That can be extremely distracting, and it can create an enormous amount of stress and pressure. You feel it every day. You only have so much time to get this many shots. The sun is moving as it continues to do to this day. And you can’t negotiate with that.

After half an hour, the couple turned it over to the audience for questions. Asked by an audience member about whether he rewatches his old work:

I don’t. I’m not brave. I’m fundamentally like, look, no, I can’t. It’s like looking at middle school pictures. I don’t want to even acknowledge that. But I do find myself having to adjust, you know.

On remastering Seven in 4K HDR:

We’re doing Seven right now. And we’re going back and doing it in 4K from the original negative. And we overscan it, oversample it, doing all of the due diligence. And there’s a lot of shit that needs to be fixed because there’s a lot of stuff that we now can add because of high dynamic range. You know, streaming media is a very different thing than 35 mm motion picture negative in terms of what it can actually retain. So, there are, you know, a lot of blown-out windows that we have to kind of go back and ghost in a little bit of cityscape out there.

While many issues may not be noticeable, on a 100-inch screen, you’ll look at it and go, ‘What the fuck, they only had money for white cardboard out there?’ So that’s the kind of stuff on print stock, it just gets blown out of being there. And now you’re looking at it, going ‘I can see, you know, 500 nits of what the fuck.’

But I’m fundamentally against the idea of changing what it is. You can fix, you know, three percent, five percent. If something’s egregious, it needs to be addressed. But, you know, I’m not gonna take all the guns out of people’s hands and replace them with flashlights.

Soderbergh: David sees things that not a lot of people see. He once invited me to a session while he was working on a film. David’s got a laser pointer and it’s frozen on the shot and he’s like, ‘I want that part of the wall a quarter of a stock darker. I walked out and laid down on a couch in the lobby because of what torture it is to see that.

On film projects involving real people, including ones who are still alive, like the subjects of his Facebook origins film, The Social Network, and the inspirations behind his Mindhunter series:

There was so much flak after Zodiac came out about people saying, ‘Why didn’t you go down this rabbit hole? Why did you only go down the Graysmith rabbit hole?’ That’s the book that we bought. We didn’t buy everyone’s book about the Zodiac.

You have a responsibility to make sure that you are saying what you want to say because chances are they can deck you in an airport. So, you want to be conscious and be smart about it. Making movies about things that are ripped from headlines is a slippery slope. I think it’s important to be responsible, and by the same token, you also have to entertain an audience.

Asked about unfinished projects like the Millenium trilogy and Mindhunter, Fincher only replied about The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo:

I was offered Dragon Tattoo long before the first movie was made and was in the middle of something else. And I was like, “lesbian hacker on a motorcycle? I don’t think so.’ And then, the thing went on to be a huge deal, and it came back around.

And so, I thought, well, it would be interesting to see if you took this piece of material that has millions and millions of people excited, and you did it within an inch of its life, could it support the kind of money that it would take to do?

And we had pledged early on that we wanted to make a movie that was not embarrassing to its Swedish heritage. We didn’t want it to seem like we just came, you know… And when they said, ‘well, can you shoot in Atlanta?’, I said, ‘no! Atlanta for Sweden? I don’t know.’ And we didn’t want to transpose it. We wanted it to be true to its essence.

And so, you shoot in Sweden. You are shooting eight-hour days, nine-hour days if you’re lucky. And so, the movie took 140 days to shoot.

And I was proud of it. I thought we did what we set out to do. I mean, I have the same reservations about whether or not, a long dead Nazi story on a remote island in the north of Sweden, would really be a gripping, ripping yarn.

But we did it the way that we could. And then when people said it cost too much for what the return on the investment was, ‘okay, swing and miss.’

An aspiring filmmaker in the audience asked about compromise and weathering disappointment in an increasingly complicated landscape:

Stick to it. It’s easier to make something now, something that looks really good, for not a lot of money. But it’s harder to get it seen. It’s harder to get bought. When I started a long time ago, it was really hard to get the money to make something, even cheaply. Because film costs money. It was hard to make stuff cheap and look good. But if you did manage to do that you had a better shot at people actually seeing it or buying it.

Another one asked for advice on how to get an independent film out in the world. Fincher deferred to Soderbergh as better suited to answering the question:

I’m a slave. I’m essentially going to beg for an inordinately huge amount of money.

Soderbergh: You have to remember everybody that you’re trying to get to, that you’re coming up against this barrier of representation, at some point got there because they were probably really good in an independent film. All you do is to continue to make something that you care about and try and get other people involved and hope that some alchemy takes place that will vault you for a moment into the space that you want to be in. It’s better now than it was. It’s not good enough. Where the democratization of technology has resulted in the fact that it’s easier to make something now, something that looks really good for not a lot of money, but it’s harder to get it seen.

And what does David Fincher watch on TV?

In terms of interfacing with movies, I think I’m like probably everybody in here, I’m the guy going through all the landing pages at Max, or Apple +, going [mimes scrolling with the remote] ‘No’, ‘Did it’, ‘Saw it!’…

I was with a friend. We meet on the weekends. And there’s a theater that we have access to, massive, great screen. And we finish watching a movie, and lights came up, and he turned to two other friends, and he goes ‘I think we’ve come to the end of content.’

Sources:

David Fincher Talks ‘Alien 3’ Mistakes, Career Evolution with Steven Soderbergh

Martin Tsai. The Wrap

David Fincher on Remastering ‘Seven’, His Least Favorite Part of Moviemaking & Why He Loves the Montage

Jill Goldsmith. Deadline

David Fincher Is Remastering ‘Seven,’ but He’s ‘Against the Idea of Changing’ What the Movie Is

Ryan Lattanzio. IndieWire

David Fincher reflects on Girl with the Dragon Tattoo: ‘Swing and a miss’

Shania Russell. Entertainment Weekly

David Fincher Opens Up About Challenges Remastering ‘Seven’ in 4K

Hilary Lewis. The Hollywood Reporter

We Can Kinda Thank Madonna for The Social Network

Jennifer Zhan. Vulture

Tribeca (Twitter)

Luz (Twitter)

Alexandra Samton (Instagram)

Patrick Tomasso (Twitter)