The DP sheds light on why they didn’t shoot on film, shooting day-for-night, and how they shot those massive dinner party scenes.

Adam Chitwood

December 8, 2020

Collider

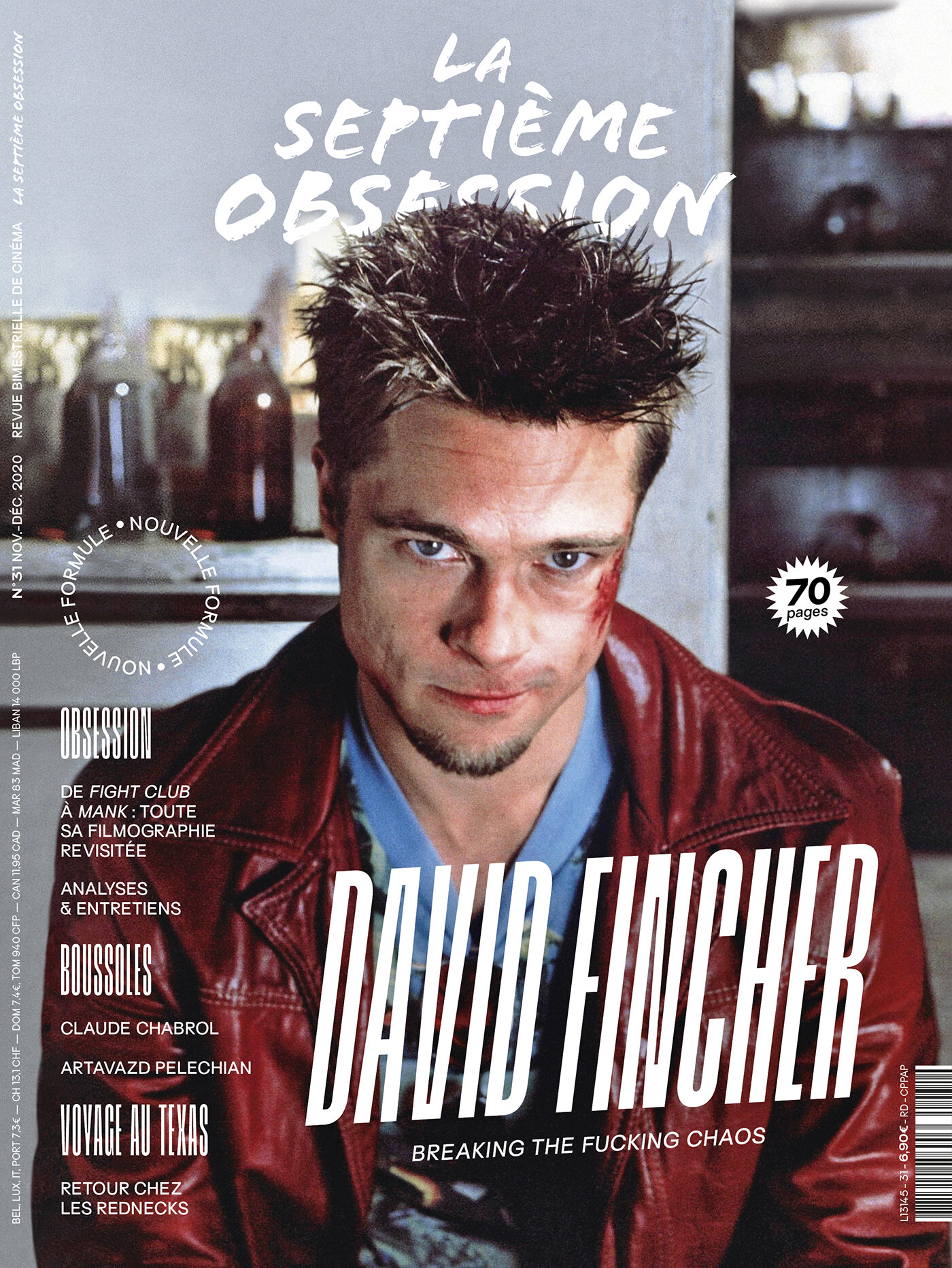

Shooting your first movie as a cinematographer is always a somewhat daunting prospect, but imagine your first movie is a 1930s-Hollywood set story about the writing of one of the greatest films ever made, boasting a cast of some of the best actors working today. Oh, and it’s in black-and-white. And the director? David Fincher.

That’s exactly what happened to Erik Messerschmidt, who got the call from Fincher that the director behind Zodiac, The Social Network, and Fight Club wanted him to be the cinematographer on his next film, Mank. The results? Absolutely stunning. Messerschmidt’s demeanor about the ordeal? Cool as a cucumber.

Messerschmidt first worked with Fincher as a gaffer on his 2014 film Gone Girl (an underrated entry in Fincher’s filmography, IMO) and then worked intimately with the filmmaker on the first two seasons of his Netflix series Mindhunter. Messerschmidt shot nearly every episode of Mindhunter, and in doing so developed a short-hand with Fincher. Which may be one of the reasons the director hired Messerschmidt to tackle one of his most visually ambitious films yet.

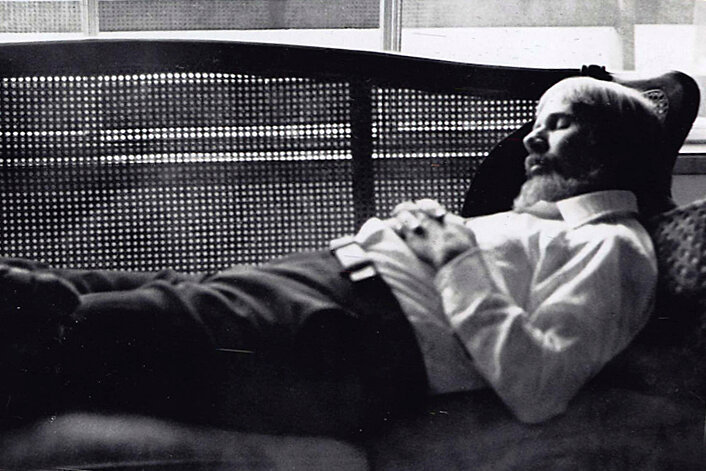

Mank takes place in Hollywood throughout the 1930s as it follows screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman) and the process by which he wrote the first draft for what would become Citizen Kane. The film alternates between Mank’s writing process and his trials and tribulations in Hollywood that would inspire some of the characters and situations in Citizen Kane, including a kinship with actress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried) and an association with publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance).

Mank is alternately jubilant and melancholic as it essentially tells the story of a talented, fun-loving writer with a knack for zingers who is somewhat changed by what he sees throughout the 1930s, and shoots his shot when Orson Welles comes a-calling.

The film is presented entirely in black-and-white with visual allusions to Citizen Kane’s groundbreaking cinematography, and when I recently got the chance to speak with Messerschmidt at length about his work on the film, he pulled back the curtain on the process through which he and Fincher brought this story to life in living monochrome.

During our 45-minute conversation, the cinematographer explained why he and Fincher never considered shooting on film, and discussed the lengthy testing process by which they ultimately found the winning formula to achieve a look that fits right in with the films made in the 30s and 40s. He also broke down the process of filming specific sequences, including Mank and Marion’s nighttime walk (shot day-for-night) and the two epic party scenes.