The Use of “Previs” in Panic Room

Nicholas Russell

January 22, 2026

Reverse Shot (Museum of the Moving Image)

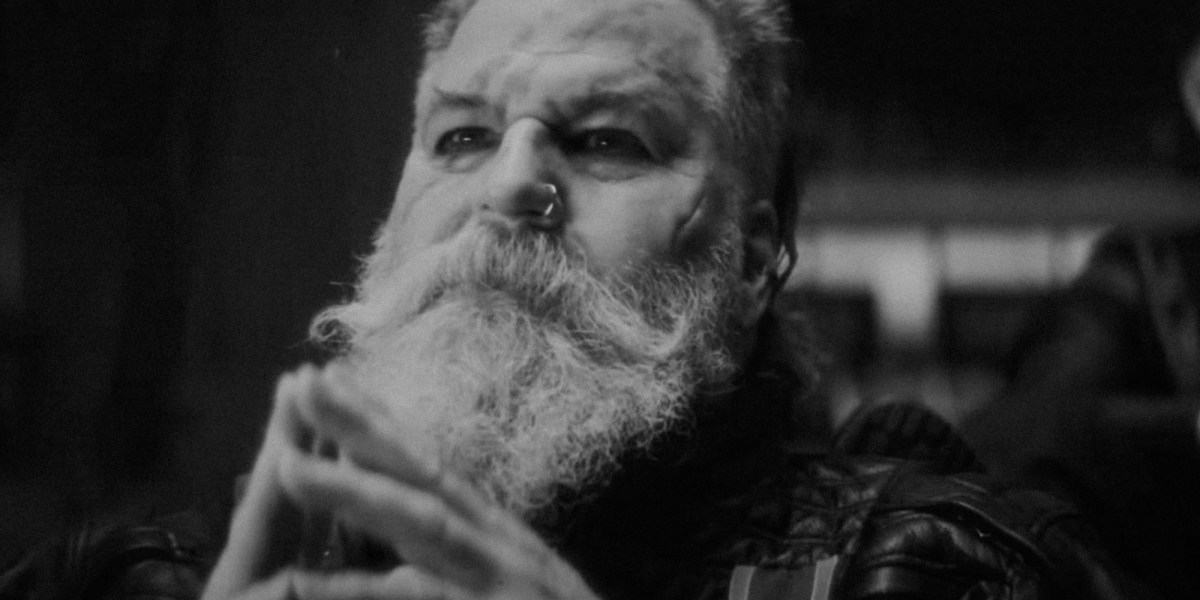

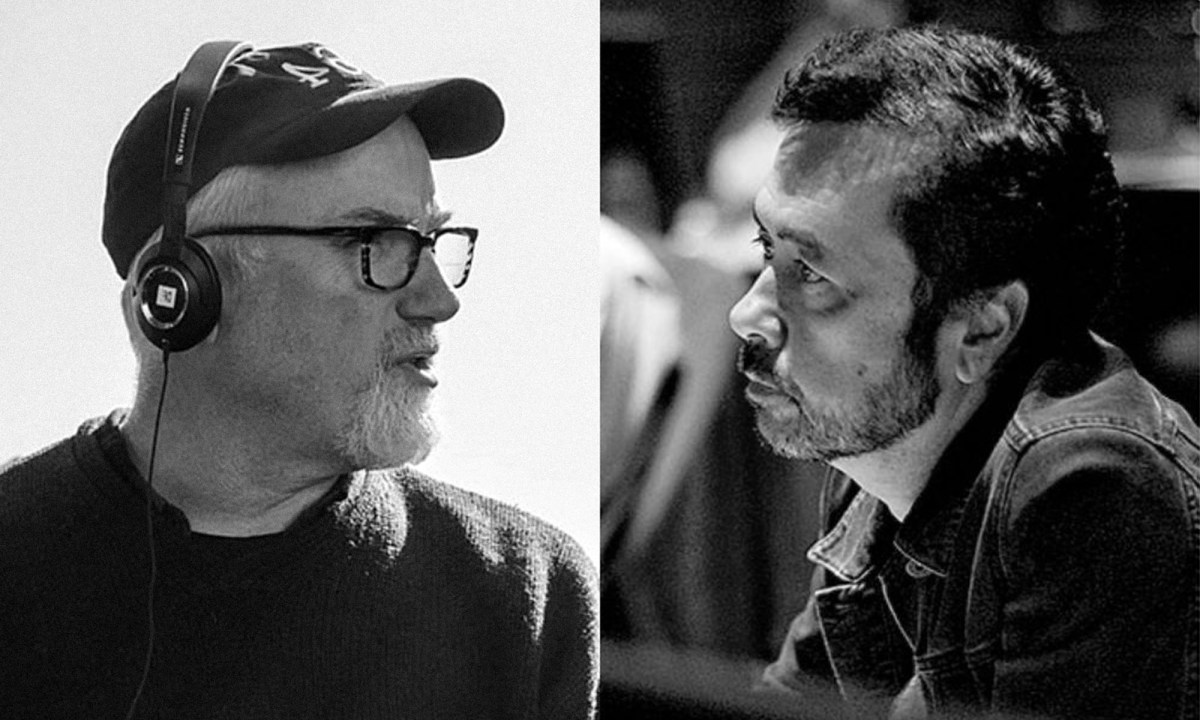

There is always a class of filmmakers perennially itching for the next technological leap forward: James Cameron and Steven Soderbergh come to mind as two directors with opposing working styles but similar ambitions for the efficiencies and reality-bending possibilities of digital technology. The transition from the photochemical film process to digital production—from cameras to visual effects to editing within the early part of the 21st century—represents one of the most profound flashpoints in cinema history. David Fincher, just as technically savvy and game to test out the latest toys, has been less has received less fanfare, but if one has paid attention to Fincher’s career for any length of time, a sentimental affinity for the medium lags far behind the more practical desire to move on to the next project. It’s one of a panoply of oft-stated advantages with digital filmmaking, the ability to move quickly and dexterously, without the literal weight of film to slow you down. But Fincher’s work, inclusive of his time in television advertising and music videos in the ’80s and ’90s, illustrates a director’s desire at first to uphold and then transcend the strictures of the camera itself.

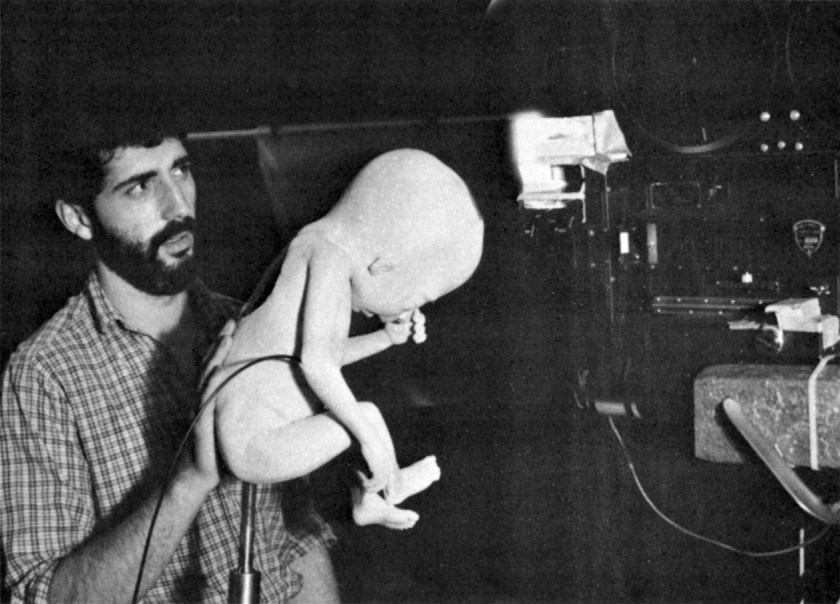

There are two competing perspectives of David Fincher: that of a hard-driving auteur who demands perfection and challenges his audiences with provocative material while still working comfortably within the commercial constraints of the Hollywood studio system; and that of the technical savant, an artist who, from a young age, steeped in the filmmaking culture of the 1970s (George Lucas was his neighbor in northern California for a time), absorbed every part of the cinematic production process, from developing film for director John Korty to working in the matte department at Industrial Light & Magic (Fincher worked under both Korty and Lucas on the 1983 animated feature Twice Upon a Time). Both views run parallel to one another throughout Fincher’s career, a gun-for-hire with an insatiable curiosity for process, a defining feature of his style and the narratives of his films.