A Legacy of Light and Shadow

Andy Nelson and Pete Wright

October 27, 2025

Movies We Like (TruStory FM)

Cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth joins Movies We Like hosts Andy Nelson and Pete Wright to explore Ridley Scott’s groundbreaking 1982 film Blade Runner. As the son of the film’s original cinematographer, Jordan Cronenweth, Jeff brings a unique perspective on both the technical achievements and lasting influence of this sci-fi noir masterpiece. With his recent work on Tron: Ares hitting theaters, Cronenweth reflects on how Blade Runner continues to inspire filmmakers and cinematographers four decades later.

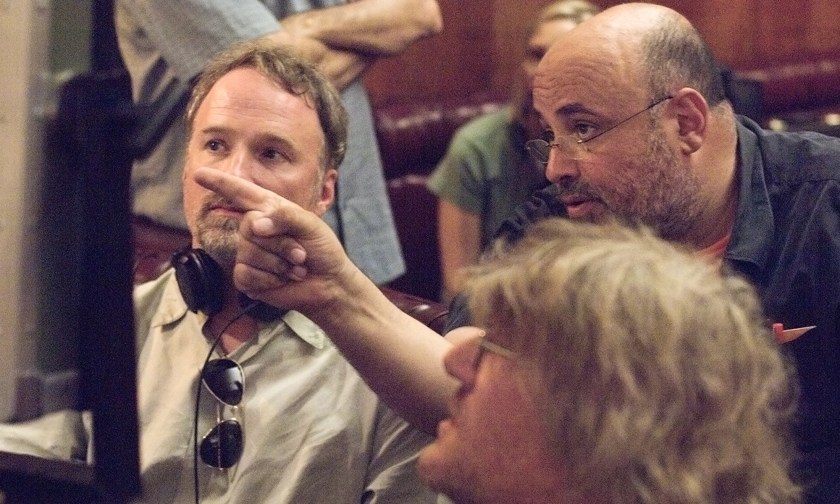

From early experiences on film sets with his father to becoming David Fincher’s go-to cinematographer on films like Fight Club, The Social Network, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Cronenweth has built a career focused on visual storytelling that serves character and narrative. He describes his approach as seeking human stories within any genre, whether period drama or science fiction. His transition from film to digital cinematography reflects broader industry changes, while maintaining his commitment to thoughtful, story-driven imagery.

The conversation explores how Blade Runner created its influential neo-noir aesthetic with remarkably limited technical resources, including just three xenon lights for its iconic beam effects and borrowed neon lights from Francis Ford Coppola’s One from the Heart set. Cronenweth shares insights into the film’s production challenges and creative solutions, from practical lighting techniques to Ridley Scott’s visionary production design. The discussion examines how the film balances its high-concept science fiction premise with intimate character moments, creating a template for genre storytelling that continues to resonate. Cronenweth also offers a perspective on the various cuts of the film and its 2017 sequel.

Through this engaging conversation, Cronenweth illuminates not just the technical mastery behind Blade Runner, but its enduring impact on cinema. His unique connection to the film through his father, combined with his own distinguished career, offers viewers fresh insights into this landmark work of science fiction and its continuing influence on visual storytelling.

Listen to the podcast: