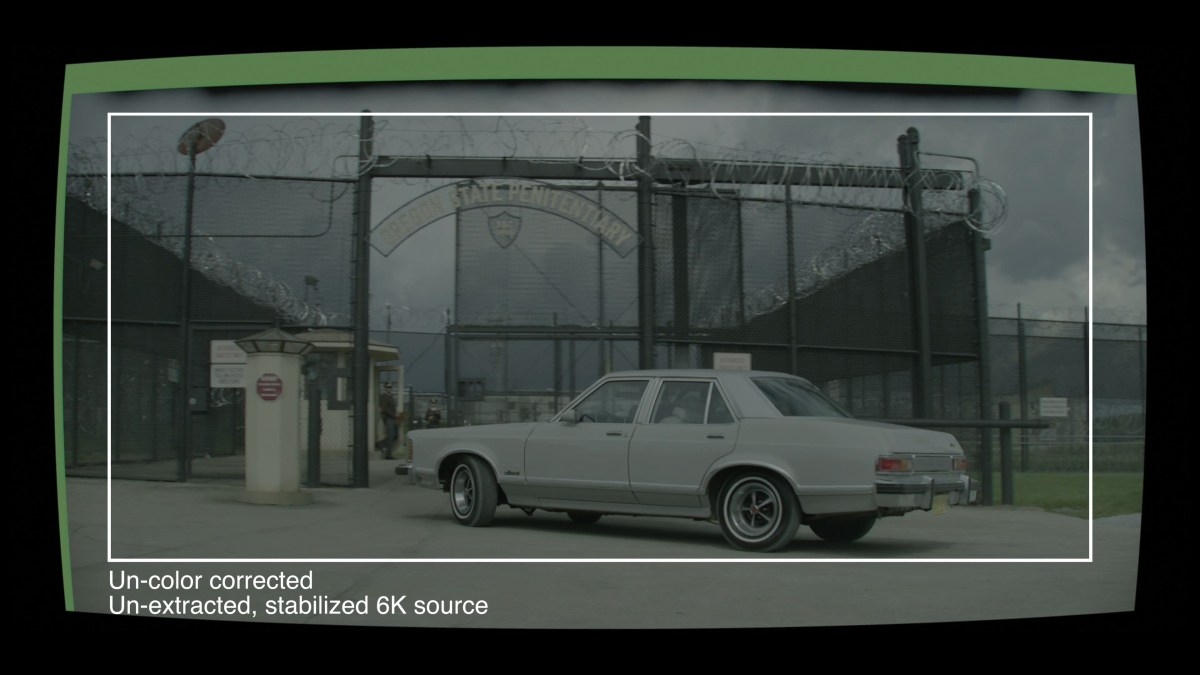

David Fincher went looking for the 1970s — and found them in Pittsburgh. but that was just the start for the esteemed producer-director and his team, who recreated the era for Mindhunter, the Netflix series about two pioneering FBI profilers.

Liane Bonin Starr

April 13, 2018

Emmys (Television Academy) / Emmy Magazine

Watching the Netflix series Mindhunter, you may shudder as convicted serial killer Ed Kemper (Cameron Britton) casually chats about his string of brutal murders, or flinch when — spoiler alert! — a bird hits the fan courtesy of mass murderer Richard Speck (Jack Erdie).

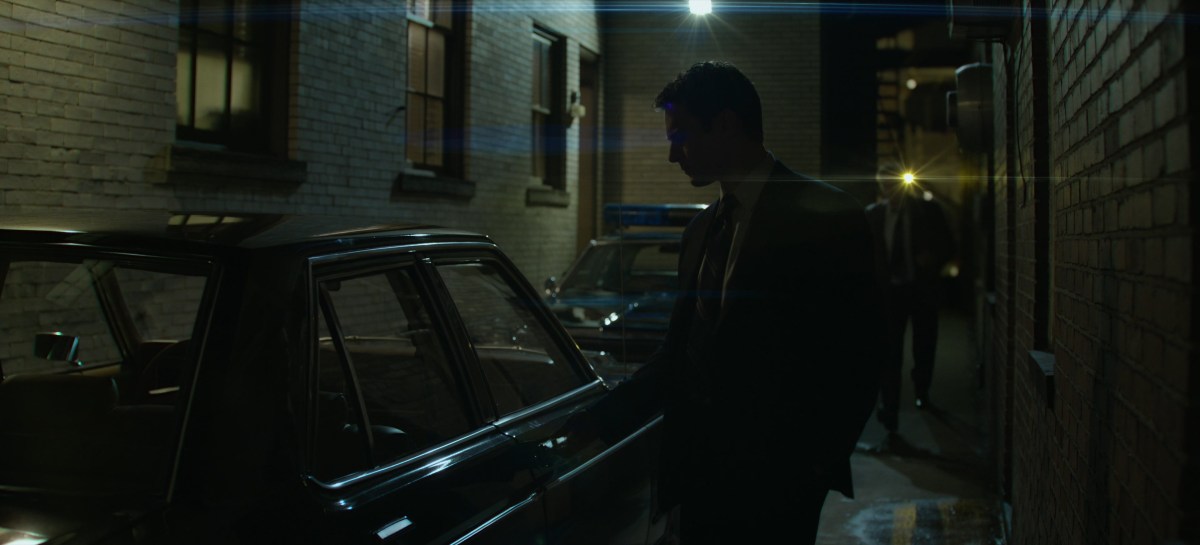

What you’re less likely to notice is the precision with which the show’s late-’70s landscape has been created. David Fincher considers that a win.

“It’s really important that it feels like two people having a conversation — and that 40 people aren’t on their iPhones simultaneously just outside of frame,” says Fincher, who is executive-producing the series with Joshua Donen, Charlize Theron and Ceán Chaffin. “The great news is, I lived through the ’70s, so I remember what that looks like.”

Created by Joe Penhall — and based loosely on FBI agent John Douglas‘s book Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit — the series explores the birth of criminal profiling.

Special agent Holden Ford (Jonathan Groff, playing a fictionalized version of Douglas) and his partner, Bill Tench (Holt McCallany), work alongside psychologist Wendy Carr (Anna Torv) to dig into what makes murderers tick. Shot in Pittsburgh, the show is a window on a time before the term serial killer had been coined, much less become the focus of TV shows and casual conversations.

While that seemingly more innocent time is reflected partly in the show’s relative lack of gore, the decade’s thornier complexities required a critical eye (or, in this case, eyes) to see past the polyester-covered clichés.

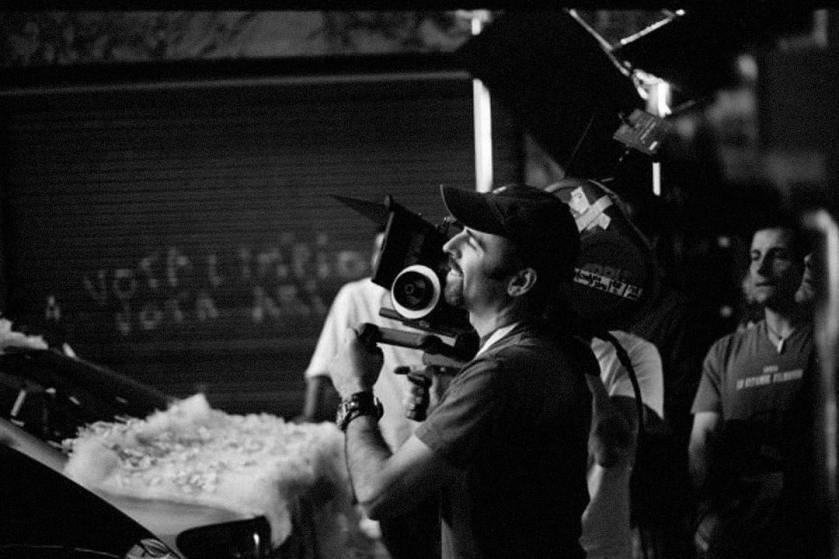

“David is the most holistic filmmaker I’ve ever met,” director of photography Erik Messerschmidt says. “The tone of every scene is important, and [so are] how the costumes and lighting and set decoration and everything play a part in creating the finished product.”

Fincher, who directed four of the first season’s 10 episodes, is famously meticulous, but he says the secret to getting it right is finding the right people.

“I don’t think you keep a project in a kind of design and aesthetic wheelhouse by being a dictatorial influence. Just stomping your feet and holding your breath is not going to make stuff work,” he says. “A lot of times, you have to empower people who are the advance troops and the follow-up troops to make decisions that are based on conversations that you have.”

In this case, one of the first decisions — where to shoot — was daunting.

“Our biggest issue,” Fincher says, “was: where do we find 1978?”

![2018-02-01 Christopher Probst, ASC (Instagram) - Ad appearing in the recent issue of American Cinematographer magazine [Ed.]](https://thefincheranalyst.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/2018-02-01-christopher-probst-asc-instagram-ad-appearing-in-the-recent-issue-of-american-cinematographer-magazine-ed1.jpg?w=840)