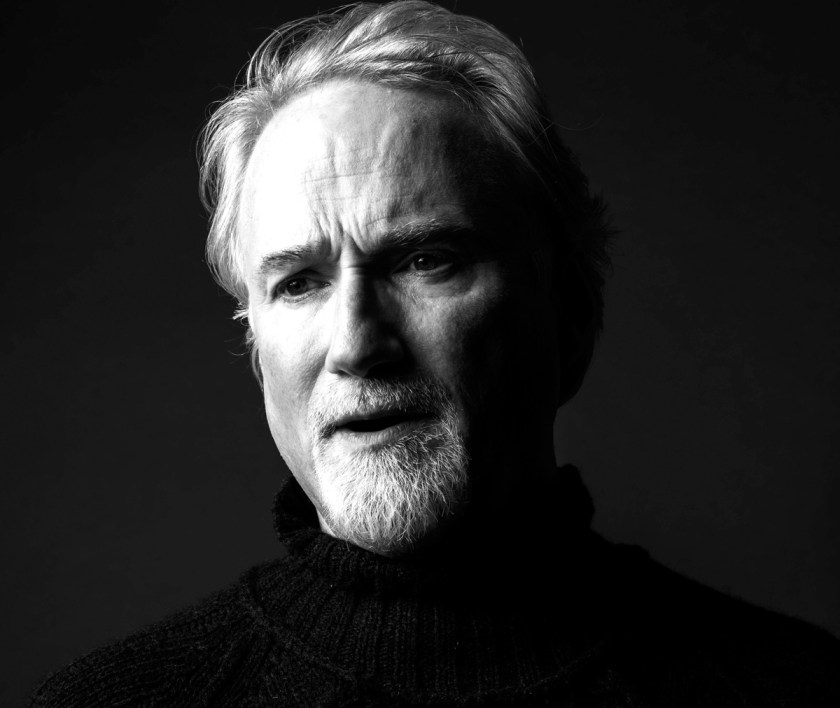

Director David Fincher looks back on how Mank made it to the screen.

Nev Pierce

February 19, 2021

Netflix Queue

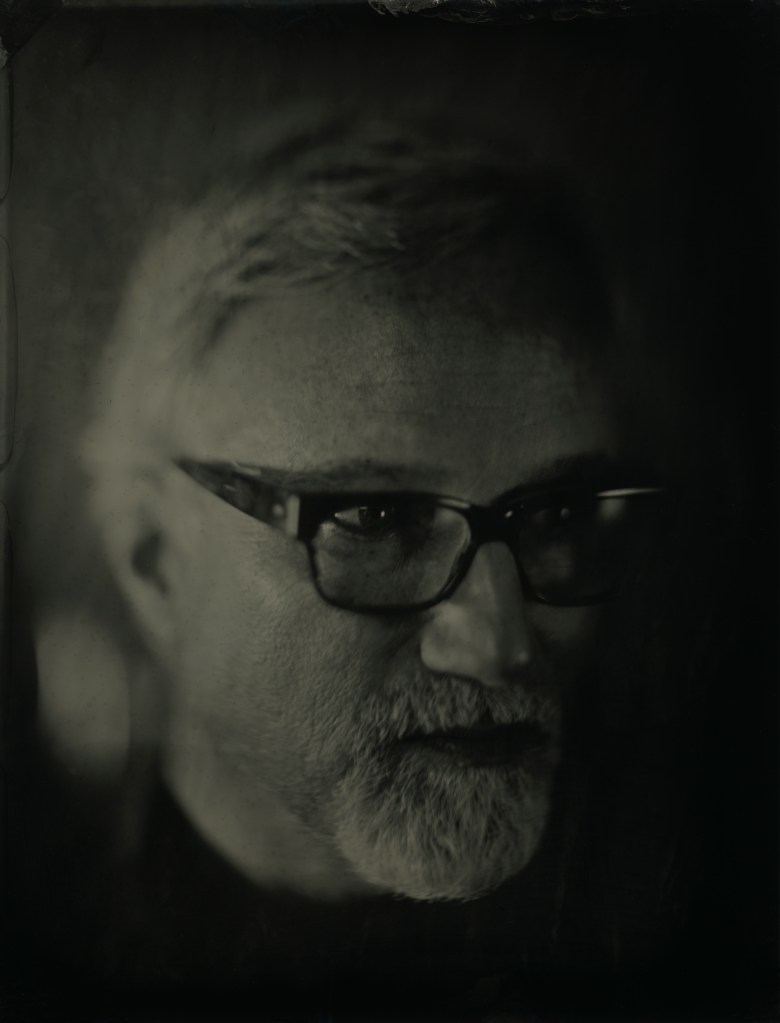

Portraits by Michael Avedon

When Jack Fincher became a parent, he shared his lifelong love of cinema, and his regard for screenwriters in particular, with his son, David. “Jack felt this was a really difficult kind of writing, and something he had great respect for,” David Fincher says, looking back. “He also believed that the beleaguered writer was not a cliché due to personality type, but because they often had to bite their tongues as they watched idiots take their ideas and mangle them.” (On that point, the Oscar-nominated director begs to differ.)

Eventually, David encouraged Jack — who was by that time retired from his journalism career — to try his own hand at screenwriting. Those efforts have now solidified into one of David Fincher’s most acclaimed films to date, a project that also serves as an homage to his father, who died from pancreatic cancer in 2003.

Mank chronicles how screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz came to pen the first draft of what would one day be Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Like so many films, Mank was years in the making, and it long loomed in David’s consciousness. Father and son initially discussed the idea in the 1990s, when David was graduating from music-video director to rising-star filmmaker. As Jack completed various revisions, they had many fruitful clashes over the direction of the screenplay.

Over the years, it became clear that the project was unlikely to see the light of day. It fell by the wayside and Jack fell ill. “He ended up having chemo to worry about, and not so much the rewrites,” David recalls. “We would talk about it from time to time. I would take him to his chemo — he was in therapy a little bit in the last couple of months of his life — and we would talk about it in the car, shoot the shit. But it was understood that this would not be something that would ever get made. And that was O.K.”

David Fincher moved forward, building an acclaimed body of work that includes Zodiac, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, The Social Network, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and Gone Girl. Ultimately he arrived at a place where he could turn his focus to that elusive project from his past. Suddenly, Mank was something that could get made, and made the way he wanted: in dazzling black and white, with a superior cast carrying it forward.

Nev Pierce spoke to David Fincher in this edited excerpt from the book Mank, The Unmaking

Read Mank, The Unmaking