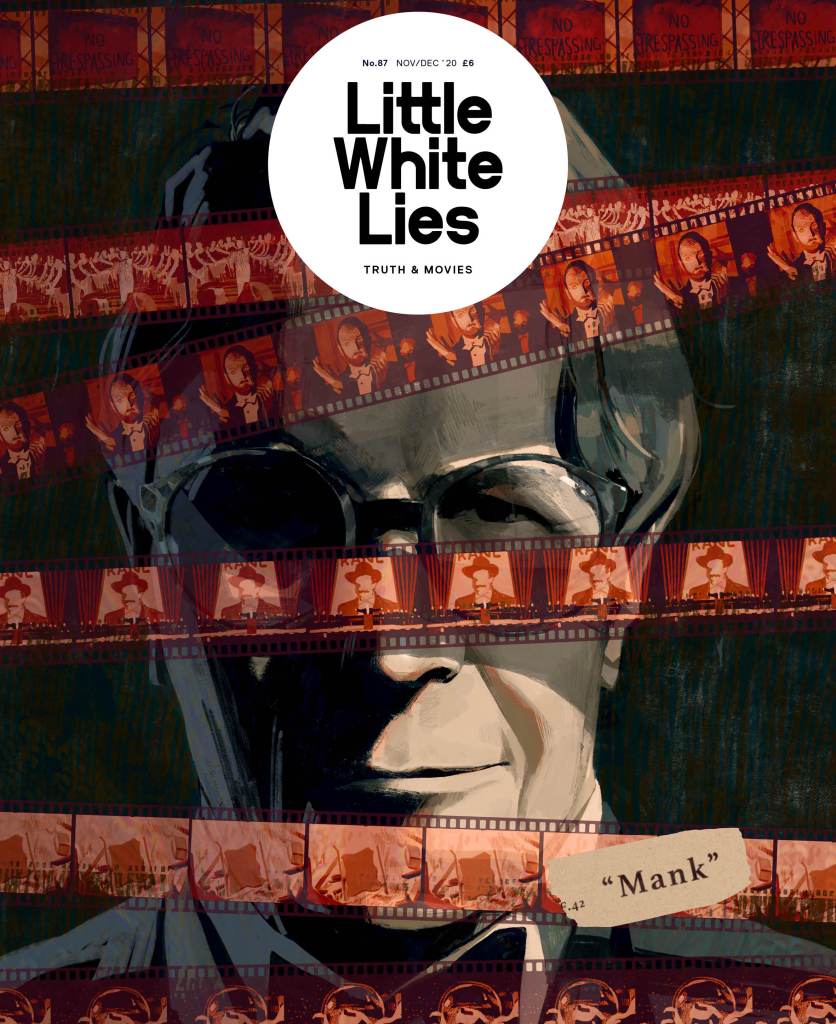

The boundary-pushing filmmaker behind ‘Mank’ reflects on his career, his journey into Hollywood’s past and the industry’s uncertain future

David Fear

January 12, 2021

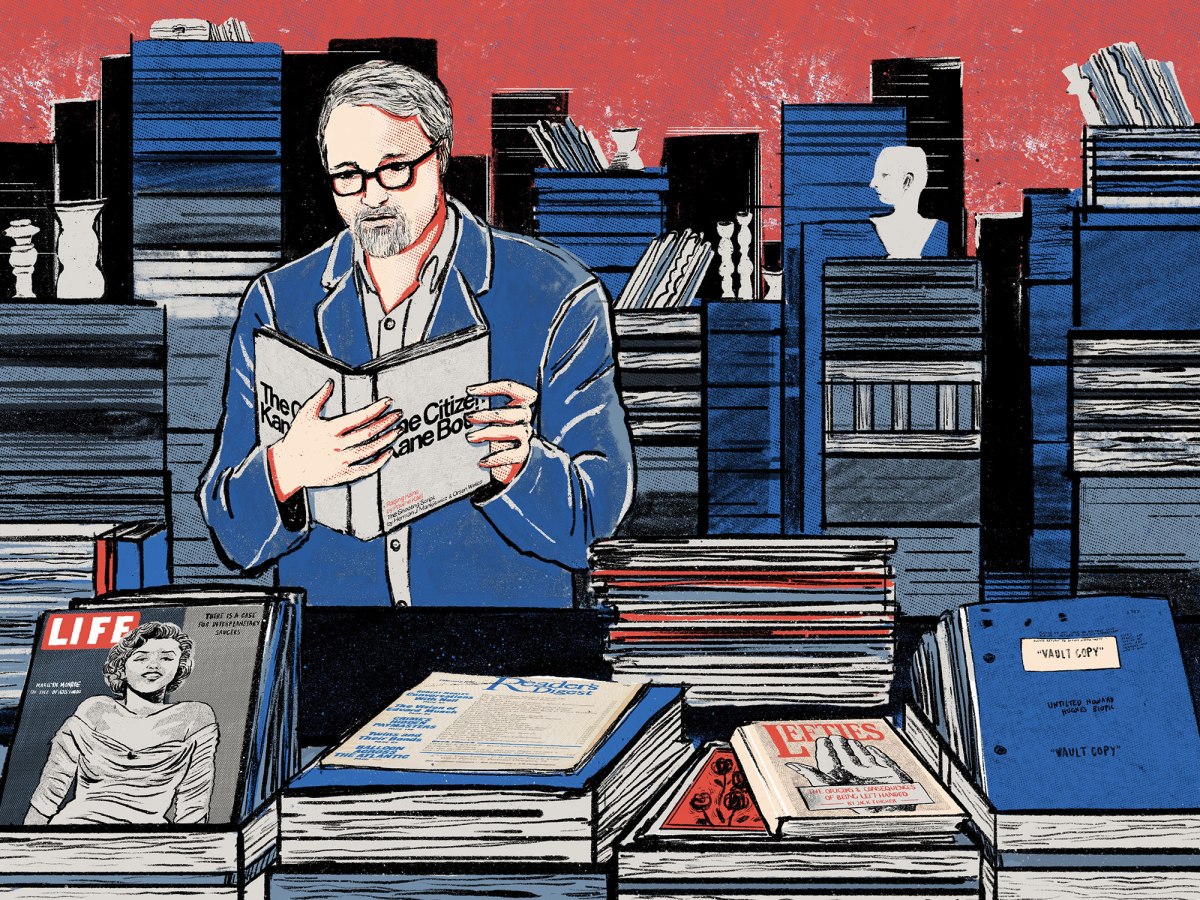

Rolling Stone

When David Fincher sat down with Netflix executives in the spring of 2019, he did not expect to be handed the equivalent of a blank check. Sure, the 58-year-old filmmaker — a former music-video wunderkind best known for pushing the envelope with baroque serial-killer thrillers (Seven), toxic-masculinity satires (Fight Club) and social-media origin stories (The Social Network) — was a name-brand director, and had helped kick off the golden age of streaming with the outlet’s first original series, House of Cards. But Fincher was used to resistance. You can’t have this budget. You can’t tell that story. What do you mean, you’re doing a TV show, for a mail-order DVD company, and all the episodes come out at once?!

So when Fincher was told by his patrons at the company that they were interested in helping him make anything he wanted, he thought of a long-dormant labor of love: a script his late father, Jack Fincher, had written about the making of Citizen Kane. Not the tale of the brilliant director, producer, star and co-writer who, at a precociously young age, took Hollywood by storm with his rise-and-fall drama. This was the story of the alcoholic screenwriter who was hired to pen the script, originally titled American, and then inserted a personal grudge against the powers that be into the greatest movie of all time.

Fincher wanted to shoot it in black-and-white. He wanted to use a lot of old-fashioned stylistic nods to Hollywood movies of the ‘40s, as if the film had just been discovered in a vault after 80 years of gathering dust. Also it would involve an obscure chapter in California’s political history concerning Upton Sinclair’s 1934 run for governor and a disinformation campaign allegedly masterminded by studio execs. It was a shot in the dark. By his own admission, Fincher couldn’t believe it when Netflix said yes.

To see Mank, Fincher’s throwback ode to the Golden Age of Tinseltown USA, however, is to know why they did. Chronicling how the broken-down writer Herman J. Mankiewicz (played by Gary Oldman) helped permanently change film as an art form, his movie is an audacious, complicated, stylistically daring and thoroughly entertaining yarn — the kind of retro nod to a bygone era that makes you feel like you’ve injected a day’s worth of TCM programming into your veins. But it’s also a challenging drama about complicity, the price of speaking truth to power and the manipulation of modern media, which couldn’t make the film feel more urgent.

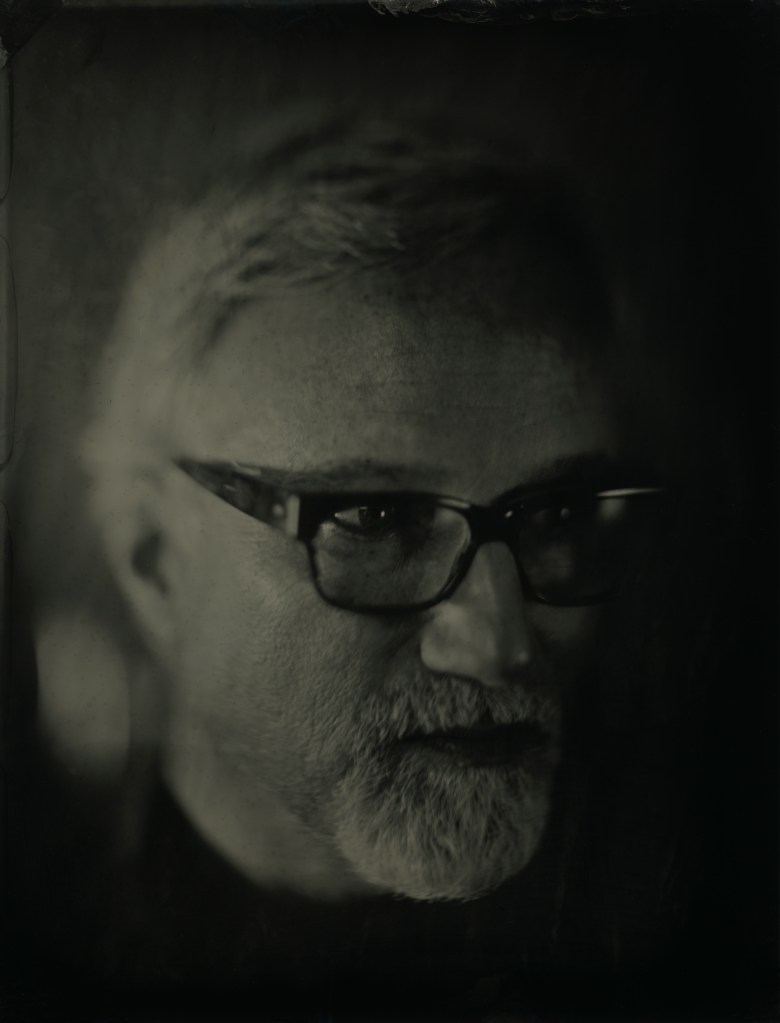

Over a two separate two-hour conversations from his home in Los Angeles, Fincher discussed bringing this tribute to his father (who died in 2003) to the screen, his reputation as a taskmaster on set, why he’s sorry Fight Club pissed off a fellow filmmaker, and more.

Wet plate ptotograph by Gary Oldman