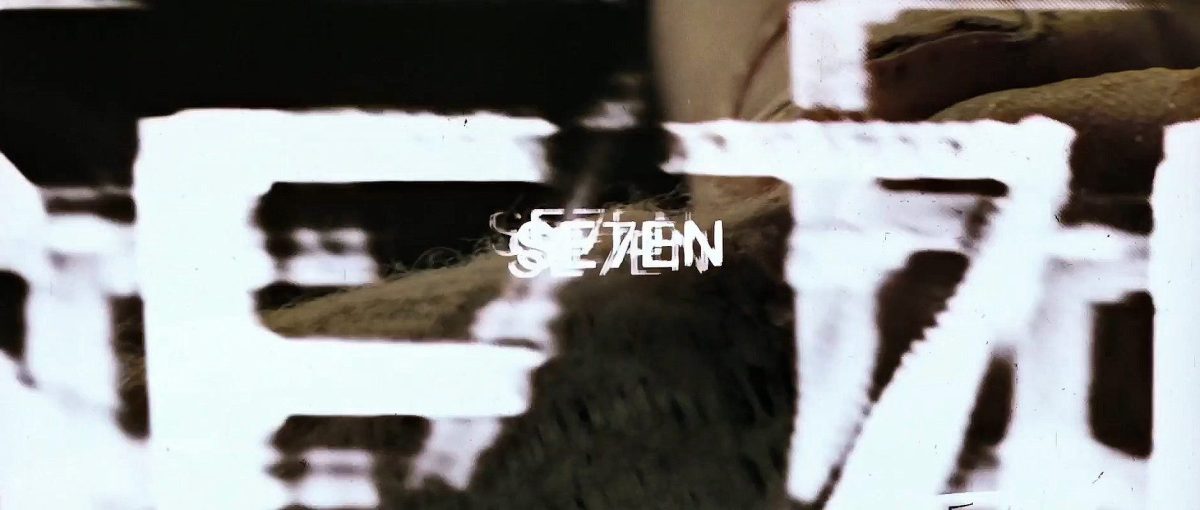

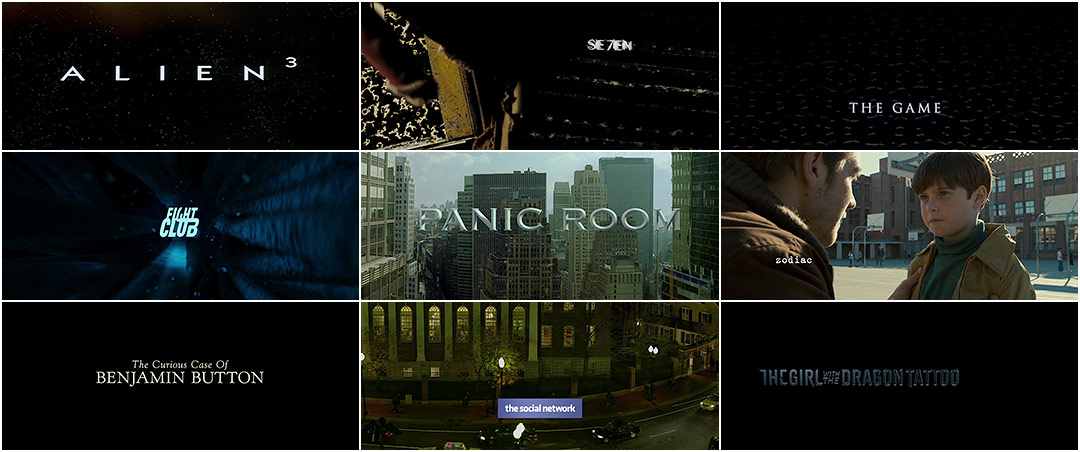

On September 22, 1995, David Fincher’s SE7EN introduced audiences to a darkness unlike anything seen before, accompanied by an opening title sequence from Kyle Cooper that has since become one of the most influential in film history.

September 26, 2025

Prologue Films (Instagram: 1, 2, 3, 4)

For this classic title sequence, David Fincher tasked Kyle Cooper, founder of Prologue Films, to get inside the mind of a serial killer, immediately setting an ominous tone. Typography was scrawled into scratch board and shot on film, and Cooper shot tabletop photography representing the preparation of the killer’s obsessive sketchbooks. This dark yet spirited sequence was called a “masterpiece of dementia” and was credited with the resurgence of a generation’s interest in film title design.

The audio of this video is pulled from Kyle’s interview on the 2010 Blu-ray Special Edition of SE7EN, where he discussed the making of the sequence in detail.

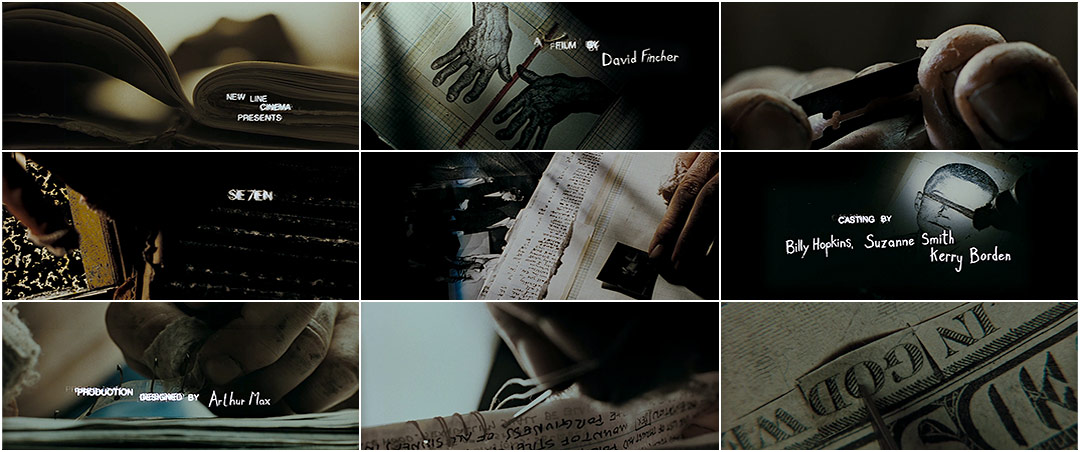

In Part 1, Kyle reflects on his early conversations with Fincher. The two bounced ideas back and forth, shaping a vision that would forever change the way opening credits were made. This reel pairs finished titles with original process photographs, every frame shot on film, every prop (from John Doe’s notebooks to the hand model) photographed and tested.

“People think there’s computer graphics in there, but we assembled the majority of the sequence by hand… it takes on a life of its own.” In Part 2, he explains how he created the unsettling typography. Every letter was scratched, smeared, and distorted through the camera itself, analogue from start to finish. This reel pairs final frames from the title sequence with the original process photography of John Doe’s notebooks, props, and hands, showing how the haunting visuals took shape long before digital tools.

“This is John Doe’s job: he gets up, makes his books, plans his murders, drinks his tea.” In part 3, he reveals how the titles were designed to immerse viewers directly into the fractured psyche of the killer. To capture the killer’s mindset, Kyle went beyond typography. He gathered real objects from his surroundings, fish hooks, razor blades, sewing needles, twine, even clumps of hair from his shower drain, and filmed them in-camera alongside hand-crafted journals. These raw analogue elements were photographed, tested, and layered into the sequence, blurring the line between prop and pathology.

Kyle has recalled in interviews that during the premiere, when the title sequence finished, the audience actually clapped, something almost unheard of for opening credits. Thirty years later, that impact still reverberates across cinema and design.

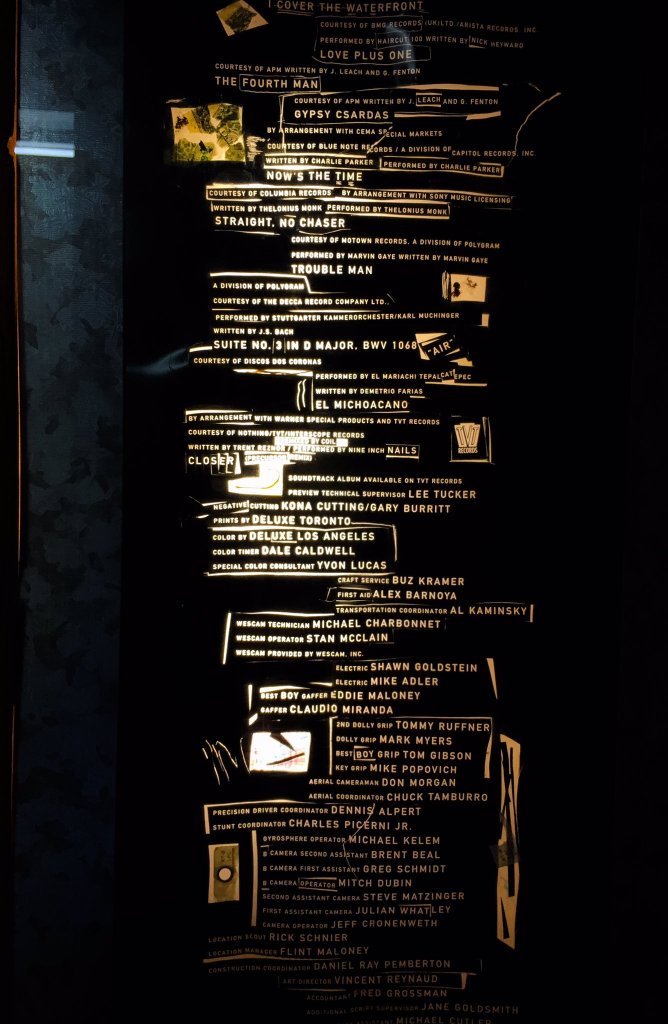

The SE7EN End Credits Crawl

The unease of SE7EN doesn’t end with the final scene. Even the closing crawl was designed to keep audiences trapped in John Doe’s world.

Kyle and Kim Cooper crafted the end credits entirely by hand. Each name was cut out and taped together into a single, massive scroll, almost like a tapestry. The piece was then shot with a video camera and lit from behind so the light bled through the lettering.

To deepen the sense of obsession, the crawl was embellished with objects John Doe might have owned: razor blades, fishing hooks, twine, screws, wire, flies, even hair pulled from a shower drain. Every detail was assembled practically, frame by frame, just like the opening titles.

We first show the original handmade scroll, now preserved in five long backlit panels at Prologue Films. Continue watching to see the crawl as it appeared in 1995. Instead of rolling upward like a traditional credit sequence, Fincher had it roll downward, a subtle inversion that mirrored the sick, twisted psychology at the heart of the film.

SE7EN end credits crawl panel, displayed at Prologue Films, photographed by Hideo Kojima.