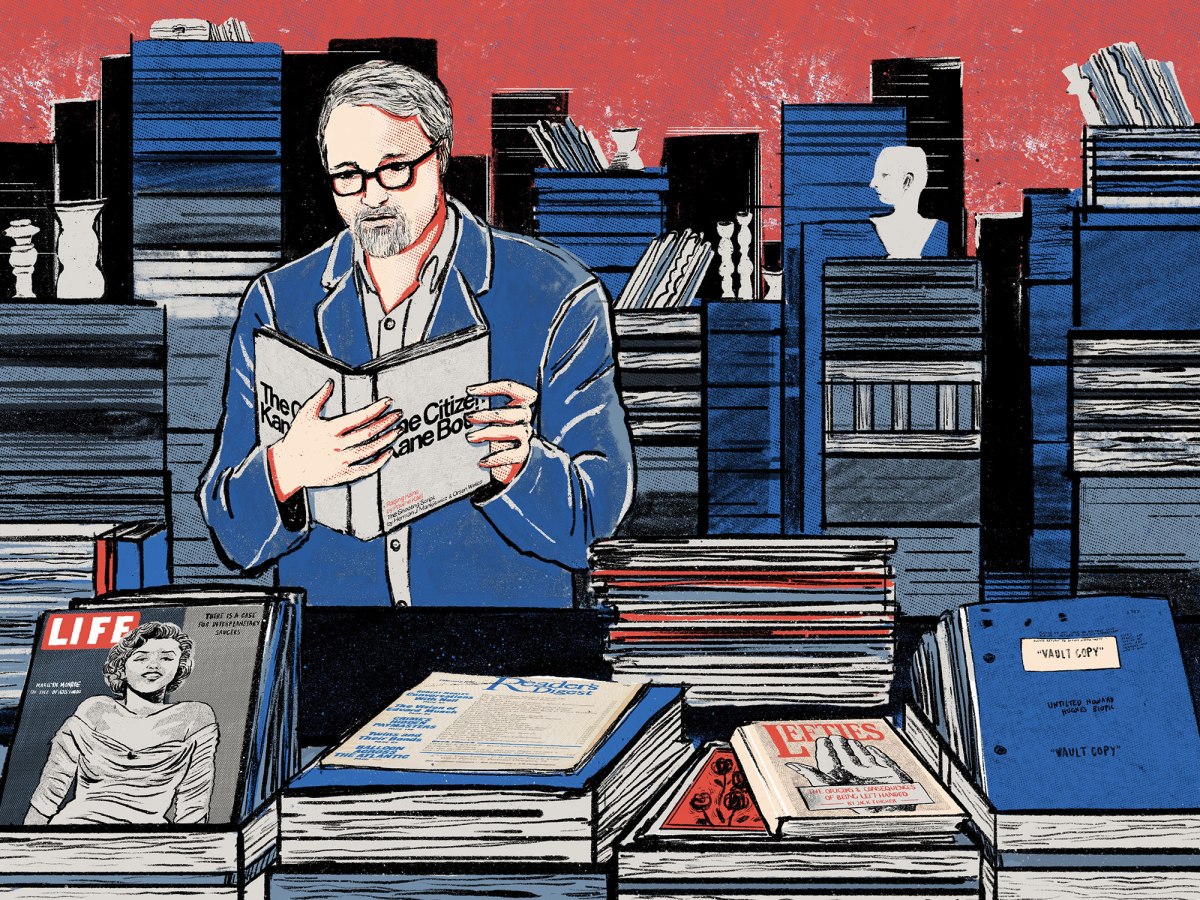

Illustration by Rumbidzai Savanhu

The master filmmaker behind Mank on Orson Welles, Pauline Kael and realising a passion project after a 30-year wait.

David Jenkins

December 2, 2020

Little White Lies

From the pen of Jack Fincher comes Mank, the story of how perma-soused Hollywood hack Herman J Mankiewicz happened to write one of the greatest screenplays of all time. Sadly, Jack didn’t live long enough to see the words he had written transformed into sound and light, but it’s something that his son David had wanted to realise for close to three decades.

It’s been six years since Fincher Jr’s last feature film, 2014’s Gone Girl, and in the interim we’ve had two series of Rolls Royce TV drama in the form of Mindhunter. For someone who has already made a tech bro riff on Citizen Kane (2010’s The Social Network), and a melancholic homage to his late father (2008’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button), Mank combines these two career poles, while also posing such existential hypotheticals as, what makes a man? And not only that, what makes a writer, and what makes a director?

LWLies: Let’s go on a quick flashback to the early days and the creation of this amazing script by your father, Jack. He was a journalist and author by trade. Did he pivot to screenwriting later in life?

Fincher: I think he wrote a screenplay that was optioned and Rock Hudson wanted to do it – this was in the late ’60s. That fizzled out. Then he wrote spec screenplays in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, and then when he retired in the ’90s, he came to me and said, ‘I’m going to have all this time on my hands, what do you want to read a script about?’ I said I had always been interested in ‘Raising Kane’ which I was exposed to in middle school. I had read Pauline Kael’s essay on microfiche in the school library, and then I noticed a copy of it in my father’s library, and we talked about it. Then, 12 years later, I was about to go off to do Alien3, and he was retiring and wanted a new challenge.

More in Little White Lies 87: The Mank Issue