The fight cannot be a lie.

October 7, 2019

Storius Magazine

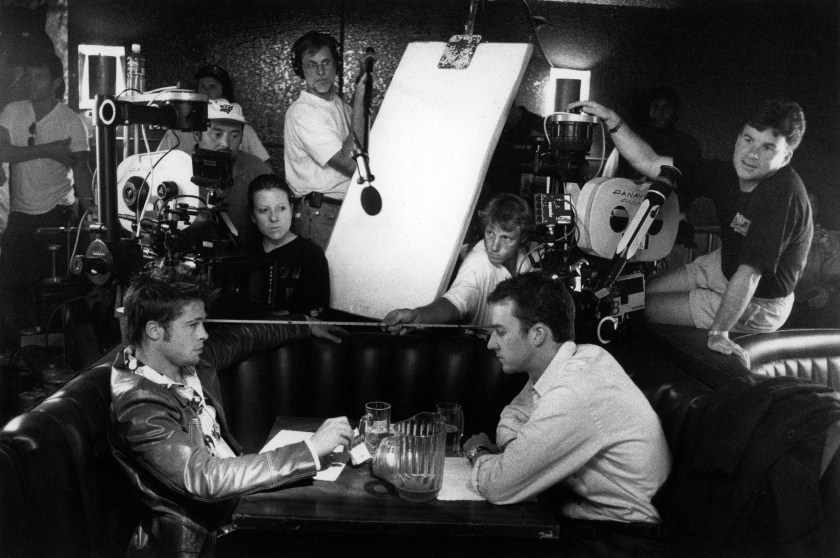

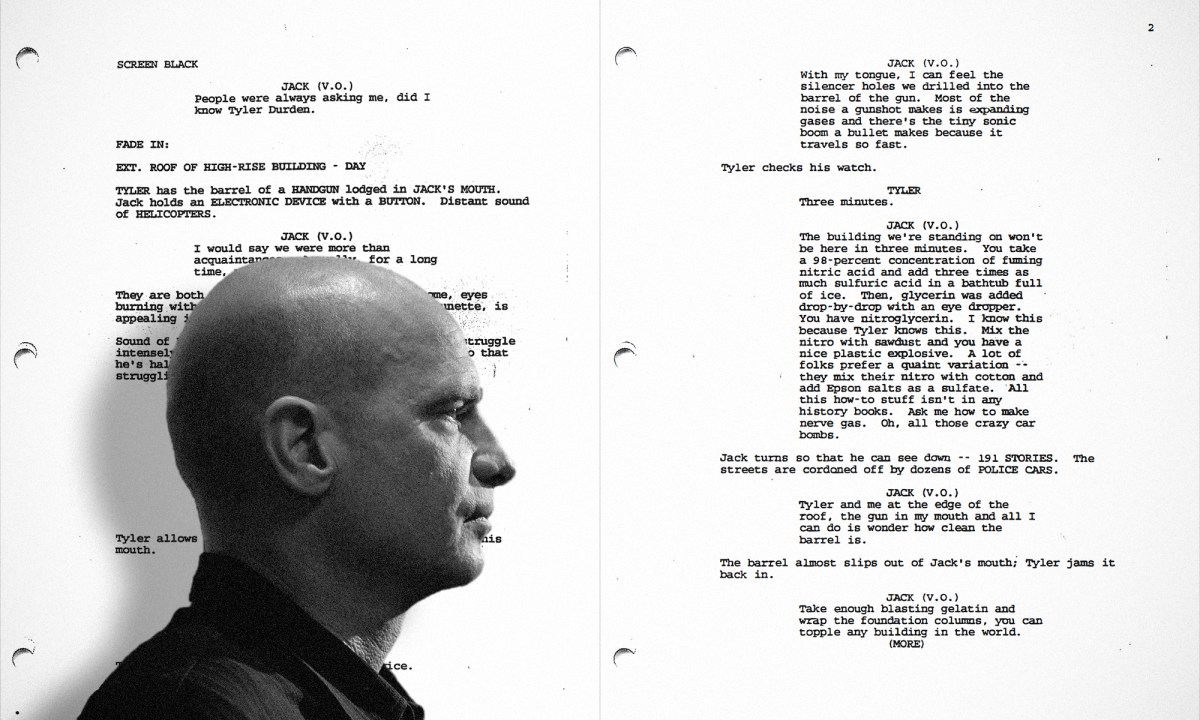

This month, Fight Club turns twenty. David Fincher’s adaptation of Chuck Palahniuk’s novel, written for the screen by Jim Uhls and starring Brad Pitt, Edward Norton, and Helena Bonham Carter, became a movie classic that has generated every form of cultural reference, from memes to research papers. Ranking #10 on IMDb’s Top 250 best-movie list and lending “The first rule of Fight Club” catchphrase to teen chats and corporate meetings alike, the film has come to occupy a unique niche in modern culture.

On the anniversary of the movie’s release, Fight Club’s screenwriter Jim Uhls spoke with Storius, reflecting on the film’s journey and lasting influence, adaptation challenges, fan theories, and his screenwriting techniques.

STORIUS: Today, twenty years after its release, Fight Club seems surprisingly contemporary, especially considering how many changes our society has gone through since 1999. It has entered the cultural lexicon, is often referenced even by people who haven’t seen it, and doesn’t seem to age much. What do you attribute the movie’s endurance to?

It hits a nerve with each generation that discovers it, seemingly because the basic life circumstances of the viewer, whether in 1999 or 2019, are the same. Part of that nerve is the idea of how self-worth is defined — both by society and in one’s mind — which are usually the same.

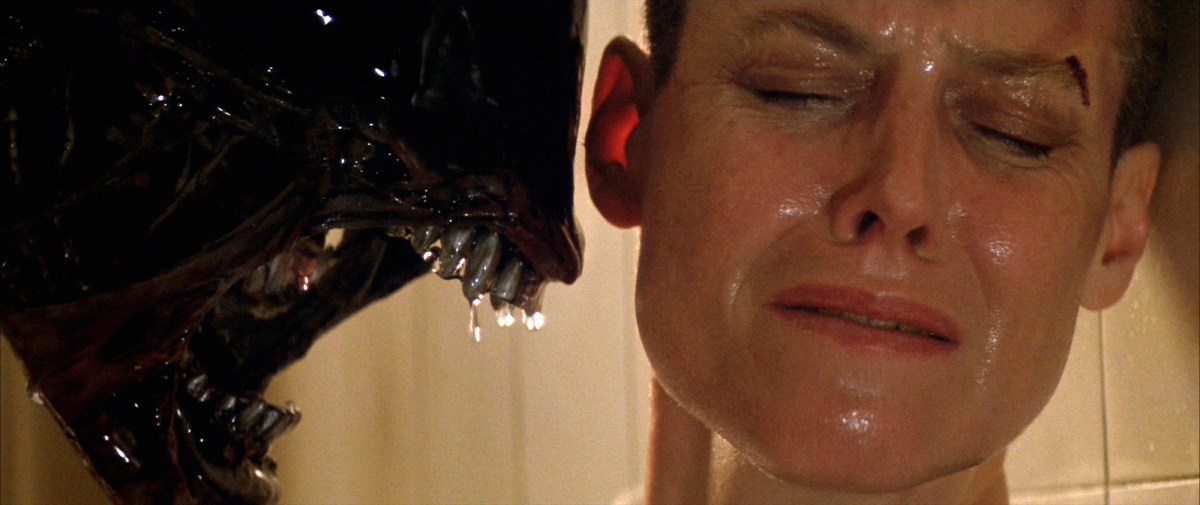

But, in this film, they become different. Men in their twenties, still puzzled about what they should do with their lives, are discovering a different way to define self-worth. A group of them meet to experience something that is outside the parameters of civilization. Each fight is one-on-one violence between two men who have no animosity towards each other, might not even know each other. They’re doing it because it’s a ritual, a primal ritual, in which they take part both by doing it and by watching others do it. It’s physical combat, wordless, and true — i.e., the fights are actually happening, so they are true. Other things all around these men can be lies, with or without words, but the fight cannot be a lie.

Another part of that nerve is Tyler Durden’s contempt for materialism, consumerism, the impossible ideals invented by advertising, and in effect — everything that is fake, or a lie, or a pathway to soullessness — all constantly bombarding us, in our “civilized” world. I’ve been repeatedly surprised by females, from teenage to senior citizens, telling me they love the film. It’s clearly aimed at a form of emancipation for young men, but part of the nerve it hits must resonate for women.

STORIUS: It’s hard to believe now that the movie was considered a failure when it was released, and that it took a few years and a DVD release to turn it into a financial success and a cultural phenomenon. Why do you think the film had such a bumpy road to recognition?

The bumpy road, the period of initial domestic release, was largely due to the vexing challenge of how to make a trailer for the film that promotes what the film is. It wasn’t an easy task. And it wasn’t achieved.

I ran into a friend about two weeks after the initial release, and he said he hadn’t gotten to the film yet, but he would; he just wasn’t a big fan of boxing movies.

“Boxing movies.” That’s a solid example of someone not having any idea of what the film was about during the time when it was vital to get that across to the public.

Read the full interview