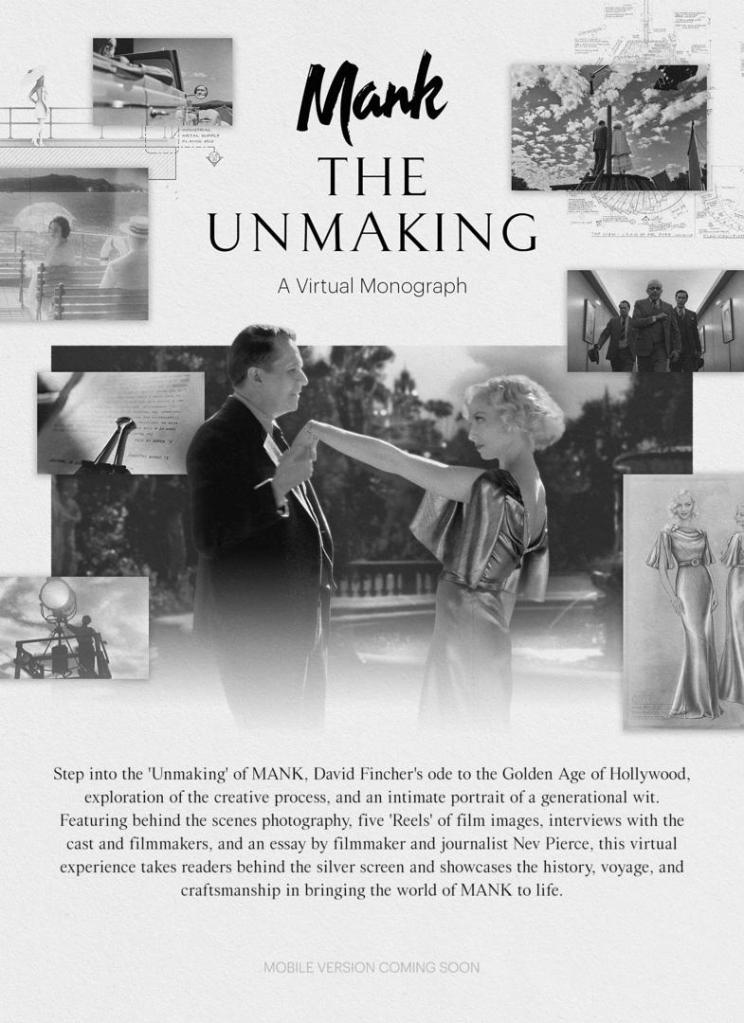

January 28, 2021

Netflix

manktheunmaking.com [Old Domain]

Text by:

Photography by:

Erik Messerschmidt

Miles Crist

Gisele Schmidt-Oldman

Gary Oldman

Ceán Chaffin

Nikolai Loveikis

Design and development by:

January 28, 2021

Netflix

manktheunmaking.com [Old Domain]

Text by:

Photography by:

Erik Messerschmidt

Miles Crist

Gisele Schmidt-Oldman

Gary Oldman

Ceán Chaffin

Nikolai Loveikis

Design and development by:

January 26, 2021

Netflix Film Club (YouTube)

Mank director David Fincher, cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt and costume designer Trish Summerville detail the approach to shooting the acclaimed slice of Hollywood history in black and white. How does the absence of color distill the visual storytelling? How do different colors in the costume and production design read when captured in black and white? Learn about all of that and more.

Casey Mink

January 21, 2021

Backstage

“Mank,” David Fincher’s new Hollywood film about old Hollywood, pays homage to its source material by shooting in black and white. But if you ask its cinematographer, Erik Messerschmidt, the Netflix feature is anything but a throwback.

How was it that you came to work on “Mank”?

I have worked with David Fincher for several years. We had done the television show “Mindhunter” together. We had developed a really good working relationship and a friendship. I met him on the film “Gone Girl”; I was the gaffer on “Gone Girl,” and I initially met David there. After we did “Mindhunter” together, we had a really good shorthand, and I made it my business to really align myself and try to figure out what it was that David wanted, and try to support him as best as I could. He and I see the world, I think, in a very similar way, at least visually. So it was very easy to be in sync in terms of which decisions are needed. We’re very rarely in opposition, and when we are, it’s a constructive one. I was so thrilled to be invited; it was like a dream.

Daniel Montgomery

January 20, 2021

Gold Derby

“I keep making this joke that it’s Fincher-vision because it’s not just black-and-white, it’s this really specific way that he’s going to light the film,” says costume designer Trish Summerville about the unique visual style of “Mank,” directed by David Fincher. The film tells the story of “Citizen Kane” writer Herman Mankiewicz, and it’s shot to resemble films of the 1930s and 1940s. That presented Summerville with equally unique challenges and opportunities. We spoke with her as part of our “Meet the Experts” costume designers panel. Watch our interview above.

“The black-and-white was the most challenging thing: figuring out how we wanted to make that work, doing different testing on clothing and fabrics … so we could see how it would read,” Summerville explains. “Even though you think you don’t need a color palette, you really do, because if not, when you’re looking at it with your naked eye on set, it becomes very jarring.” And understanding color was crucial for achieving the right effect in the finished product “so that when it read in black-and-white on the screen and on the monitors it didn’t just all come across as flat, it had dimension to it, sheens and tones.”

It helped that the film was portraying so many well-known figures with documented looks and styles — not just Mankiewicz, but Marion Davies, William Randolph Hearst, Louis B. Mayer, and more. “We could find things of [Mank] at work, on sound stages, and also at home,” Summerville says. “We even at one point found these images of him at one of his kids’ bar mitzvahs, so that was great, it was a whole family photo.”

But in a film with so many male characters, it was also important “to give each one of the men their own kind of characteristics and dress them towards who those characters really were … so that not everybody read as a navy suit in a room.” That research and detail, in collaboration with Fincher’s direction, Donald Graham Burt‘s production design and Erik Messerschmidt‘s cinematography, “all of it has these special touches that make you feel you’re transported to the 1930s.”

J.D. Connor

January 13, 2021

Film at Lincoln Center

With his transfixing digital black-and-white cinematography, DP Erik Messerschmidt, ASC, breathes gorgeous life into the world of 1930s Hollywood in Mank, David Fincher’s vivid retelling of the genesis of Citizen Kane and the tumultuous partnership between screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz and director-star Orson Welles.

Messerschmidt joined us for an extended conversation to discuss the craft behind Mank, the legacy of Citizen Kane, and the work of visualizing Hollywood’s ideas of itself. The discussion will be moderated by J.D. Connor, Associate Professor of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California.

Film at Lincoln Center Talks are presented by HBO.

Film at Lincoln Center on: YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

“You don’t want it to be a parlor trick”

Matt Grobar

January 11, 2021

Deadline

On David Fincher’s Mank, cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt channeled the aesthetics of Hollywood’s Golden Age, in order to tell the story of one of its legendary figures.

Written by Fincher’s late father, Jack, the drama follows brilliant, alcoholic screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman), as he pens the script for Citizen Kane.

Shooting digitally, in native black and white, Messerschmidt would place viewers inside Mankiewicz’s era by playing with the vocabulary of films from the ’30s and ’40s. At the same time, he would look to pay homage with his choices to Gregg Toland, the pioneering DP behind Kane, who popularized deep focus photography. “I think it was more [loose] inspiration, and we certainly weren’t recreating anything from Citizen Kane directly,” Messerschmidt notes. “When I was feeling insecure about the choices I was making, I’d be like, ‘Okay, what would Gregg Toland have done?’ But we were certainly making our own movie.”

After collaborating with the younger Fincher on his serial killer drama, Mindhunter, Messerschmidt was well prepared to take on the demands of this passion project, which he’d been looking to bring to the screen since the beginning of his career. “You know, David is interested in the pursuit of excellence,” he says, “so we are endeavoring for that on every take.”

At the same time, the project was intimidating, on a certain level—the challenge being to bring period style to Mank, without ever taking it over the top. Below, the DP breaks down his approach to shooting the Oscar contender, which marks his first narrative feature, along with the many highlights of his experience on set.

The director had to employ digital advances to achieve a vintage aesthetic in telling the tale of ‘Citizen Kane’ screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz: “If we had done it 30 years ago, it might’ve been truly a bloodletting.”

Rebecca Keegan

January 11, 2021

The Hollywood Reporter

Screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz never sought credit for conceiving one of the all-time great ideas in the history of cinema — the notion that the Kansas scenes in The Wizard of Oz should be shot in black and white and the Oz scenes in color. In fact, for much of his career in Hollywood from the late 1920s to the early ’50s, Mankiewicz seemed to view his scripts with about as much a sense of ownership as a good zinger he had landed at a cocktail party.

But what fascinated David Fincher was that when it came time to assign credit on the screenplay for Citizen Kane, which Mankiewicz wrote with Orson Welles in 1940 (or without, depending on your perspective), the journeyman screenwriter suddenly and inexplicably began to care. Precisely why that happened is the subject of Fincher’s 11th feature film, Mank.

“I wasn’t interested in a posthumous guild arbitration,” Fincher says of Mank, which takes up the Citizen Kane authorship question reinvigorated by a 1971 Pauline Kael essay in The New Yorker. “What was of interest to me was, here’s a guy who had seemingly nothing but contempt for what he did for a living. And, on almost his way out the door, having burned most of the bridges that he could … something changed.”

Shot in black and white and in the style of a 1930s movie, Mank toggles between Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman) writing the first draft of Citizen Kane from a remote house in the desert and flashback sequences of his life in Hollywood in the ’30s, including his friendship with newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance), who inspired Citizen Kane, and Hearst’s mistress, actress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried).

A filmmaker known for his compulsive attention to detail, Fincher had even more reason than usual to treat every decision with care on Mank, as he was working from a screenplay written by his father, journalist Jack Fincher, who died in 2003. Jack had taken up the subject in retirement in 1990, just as David was on the eve of directing his first feature, Alien 3, and the two would try throughout the 1990s to get the film made, with potential financiers put off by their insistence on shooting in black and white.

Cinefade VariND

January 7, 2020

Cinefade is a motorised variable ND filter that allows cinematographers to gradually transition between a deep and a shallow depth of field in one shot at constant exposure to accentuate a moment of extreme drama in film or to make a client’s product stand out in commercials.

It can also be used in VariND mode to achieve interior to exterior transition shots without ‘riding the iris’ and to control reflections on automotive shoots with the remotely controlled RotaPola.

Director of Photography Erik Messerschmidt ASC used the Cinefade VariND not only as a practical tool to control exposure on set but also as a storytelling tool to accentuate certain moments and guide the viewer’s attention.

Director: David Fincher

Director of Photography: Erik Messerschmidt ASC

A Camera First Assistant: Alex Scott

Erik Messerschmidt ASC to Filmmaker Magazine:

“We also used this tool called the cmotion Cinefade. It’s a motorized polarizer that you sync to the iris so we could effectively pull depth of field. It’s quite extreme. You could pull five stops of depth of field. So we could go from a T8 to a 2. That thing kind of lived on the camera. There were times where we’d say, “It’s too much. Let’s look at it at a 5.6.” So you set the iris to a 5.6, the polarizer compensates and now you’re looking at the same scene but with less depth of field. So, it was nice to be able to use focus and iris as a storytelling tool instead of just an exposure tool.”

Danny Boyd

December 13, 2020

CinemaStix (YouTube)

Today, let’s dive into the filmmaking mind of director David Fincher, and his 2020 film Mank.

David Fincher loves CGI and VFX, and that is on full display just as much in Mank (2020) as it is in all his past films. Only this time, for Mank, David Fincher had to use those tools, along with an old school cinematography and directing style, and smart editing, not only to create a convincing 1930’s Hollywood world, reminiscent of movies like Orson Welles‘ Citizen Kane, but also a convincing golden age Hollywood movie. Let’s see how David Fincher faked Mank.

Video written & edited by Danny Boyd (Instagram). Support me on Patreon.

David Fincher brings the big screen to us for his latest picture. With a cast led by Gary Oldman & Amanda Seyfried, is Mank a love letter to cinema’s golden age or an indictment of the shadier side of the movie biz?

Joe Utichi

January 6, 2021

Awardsline (Deadline)

Read the full issue of Deadline Presents Awardsline

The Burning Question That Drove David Fincher’s Decades-Long Journey To Make ‘Man

Joe Utichi

January 6, 2021

Deadline

David Fincher turns Netflix homes into 1940s movie houses with his latest opus, Mank, which explores the life and frustrations of Citizen Kane’s screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, as he works his way through the draft of what will become Orson Welles’ seminal directorial debut. With its title role imbued with Mankiewicz’s world-weary wit by Gary Oldman, and from a script first drafted more than 20 years ago by Fincher’s father Jack, who passed away in 2003, the film reignites the debate about the authorship of a film Welles might nearly have taken sole credit for. But it is about more than that besides; a love and hate letter to the machinations of the movie business, a remarkably timely examination of the façade of truth in the news media, and an intimate study of tortured souls beaten down by the world around them and their own insecurities. Joe Utichi meets Fincher, Oldman and Amanda Seyfried—who rehabilitates the image of actress and socialite Marion Davies—for a closer look.