Dan Evans (The Ringer)

In an excerpt from the new book ‘Best. Movie. Year. Ever.,” David Fincher, Edward Norton, and the minds behind ‘Fight Club’ talk about the bare-knuckled, bloody battle to bring Chuck Palahniuk’s book to the big screen

Brian Raftery

March 26, 2019

The Ringer

Sometimes, during their breaks, the men who worked alongside Chuck Palahniuk would gather to talk about where their lives had gone wrong. It was the early nineties, and Palahniuk was employed at a Portland, Oregon, truck-manufacturing company called Freightliner. Many of his colleagues were well-educated, underutilized guys who felt out of sorts in the world—and they put the blame on the men who’d raised them. “Everybody griped about what skills their fathers hadn’t taught them,” says Palahniuk. “And they griped that their fathers were too busy establishing new relationships and new families all the time and had just written off their previous children.”

Palahniuk’s Freightliner duties included researching and writing up repair procedures—tasks that required him to keep a notebook with him at all times. At work, when no one was looking, he’d jot down ideas for a story he was working on. He’d continue writing whenever he could find the time: between loads at the laundromat or reps at the gym or while waiting for his unreliable 1985 Toyota pickup truck to be fixed at the auto shop. The result was a series of “small little snippets” about an unnamed auto company employee who’s so spiritually inert, so unsatisfied, that he finds himself attending various cancer support groups, just to unnumb himself. He soon succumbs to the atomic charisma of Tyler Durden, a mysterious figure whose name had been partly inspired by the 1960 Disney movie Toby Tyler. “I grew up in a town of six hundred people,” says the Washington-born Palahniuk, “and a kid in my second-grade class said he’d been the actor in that movie. Even though he looked nothing like him, I believed him. So ‘Tyler’ became synonymous with a lying trickster.”

After meeting Tyler Durden, Palahniuk’s narrator begins attending Fight Club, a guerrilla late-night gathering in which men voluntarily beat each other bloody. Fight Club comes with a set of fixed rules, the most important of which is that, no matter what, you do not talk about Fight Club. Many of the book’s brawlers are working-class guys with the same dispiriting jobs—mechanics, waiters, bartenders—held by some of Palahniuk’s friends. “My peers were conflict averse,” says Palahniuk. “They shied away from any confrontation or tension, and their lives were being lived in this very tepid way. I thought if there was some way to introduce them to conflict in a very structured, safe way, it would be a form of therapy—a way that they could discover a self beyond this frightened self.”

Palahniuk would bring work-in-progress chapters to writing classes and workshops around Portland, holding one successful early reading at a lesbian bookstore. “They wanted to know ‘Is there a women’s version of this?’ he says. “They just assumed Fight Clubs existed in the world and wanted to participate.” Palahniuk, then in his early thirties, had recently seen his first novel get rejected. “I was thinking ‘I’m never getting published, so I might as well just write something for the fun of it.’ It was that kind of freedom, but also that kind of anger, that went into Fight Club.” He’d wind up selling the book to publisher W. W. Norton for a mere $6,000.

Fight Club’s quiet 1996 release came just a few years after the arrival of the so-called men’s movement, in which dissatisfied dudes looking to reclaim their masculinity would gather for all-male retreats in the woods. They’d bang drums and lock arms in the hope of escaping what had become a “deep national malaise,” noted Newsweek. “What teenagers were to the 1960s, what women were to the 1970s, middle-aged men may well be to the 1990s: American culture’s sanctioned grievance carriers, diligently rolling their ball of pain from talk show to talk show.”

Palahniuk’s Fight Club characters, though, were younger and angrier than their aggrieved elders. A few primal scream sessions in the woods weren’t going to cut it. “We are the middle children of history, raised by television to believe that someday we’ll be millionaires and movie stars and rock stars, but we won’t,” Tyler says of his peers, adding “Don’t fuck with us.” It was one of many briskly written yet impactful mission statements in Palahniuk’s book, which earned positive reviews from a few major critics—the Washington Post called it “a volatile, brilliantly creepy satire”—as well as the author’s own father. “He loved it,” Palahniuk says. “Just like my boss thought I was writing about his boss, my dad thought I was writing about his dad. It was the first time we really connected. He’d go into these small-town bookstores, make sure it was there, and brag that it was his son’s book.”

Fight Club wasn’t an especially big performer in its original hardcover run, selling just under 5,000 copies. But before it even hit shelves, an early galley copy reached producers Ross Grayson Bell and Joshua Donen, the latter of whom had produced such films as Steven Soderbergh’s noir The Underneath. Bell was put off by some of the book’s violence, but as he read further, he arrived at Fight Club’s big revelation: the insomniac narrator, it turns out, really is Tyler Durden, and at night he’s been unknowingly leading the Fight Club army raiding liposuction clinics for human fat—first to turn into soap, and then to use for explosives. Eventually Tyler’s hordes of followers begin engaging in a series of increasingly violent acts. “You get to the twist, and it makes you reassess everything you’ve just read,” says Bell. “I was so excited, I couldn’t sleep that night.” Looking to make Fight Club his first produced feature, Bell hired a group of unknown actors to read the book aloud, slowly stripping it down and rearranging parts of its structure. He sent a recording of their efforts to Laura Ziskin, who’d produced Pretty Woman and was now heading Fox 2000, a division that focused on (relatively) midbudget films. According to Bell, after listening to his Fight Club reading during a fifty-minute drive to Santa Barbara, Ziskin hired him as one of Fight Club’s producers. “I didn’t know how to make a movie out of it,” said Ziskin, who optioned the book for $10,000. “But I thought someone might.”

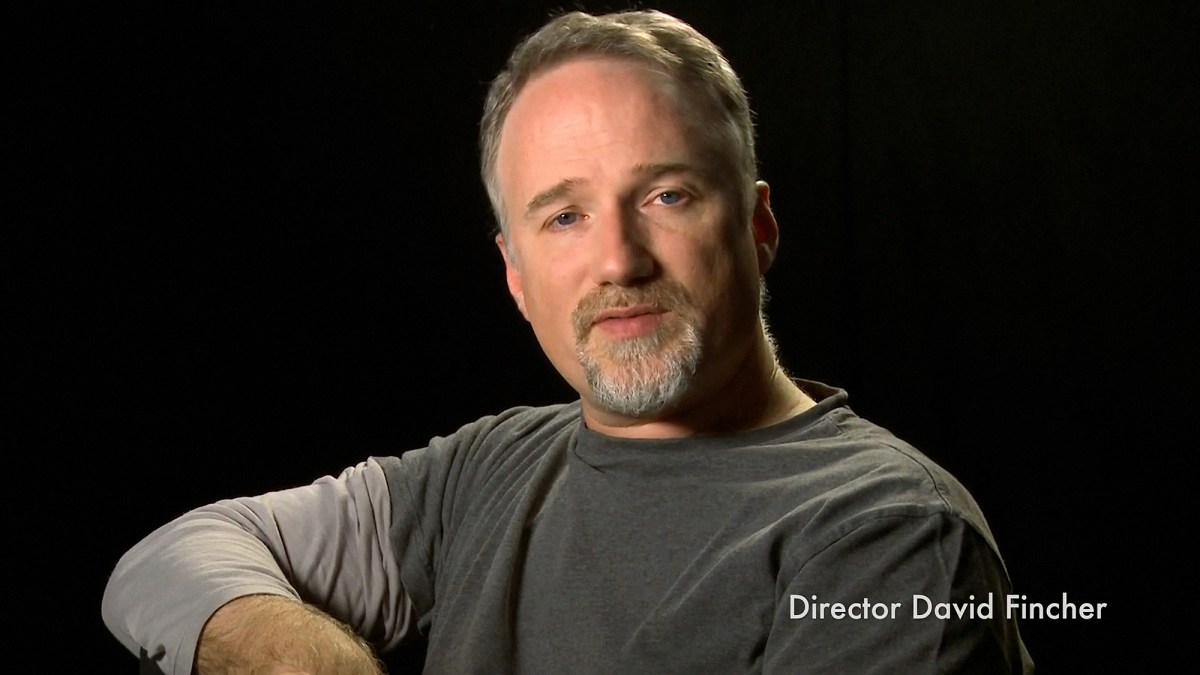

Ziskin gave a copy of Palahniuk’s book to David O. Russell, who declined. “I read it, and I didn’t get it,” Russell says. “I obviously didn’t do a good job reading it.” There was one filmmaker, though, who definitely got Fight Club. He was the perfect match—a guy who viewed the world through the same slightly corroded View-Master as Palahniuk; who could attract desirable actors; who could make all of Fight Club’s bodily fluids splatter beautifully across the screen. And he wasn’t afraid of drawing a little blood himself.

The Ringer: The 50 Best Movies of 1999, Part 1

The Ringer: The 50 Best Movies of 1999, Part 2

Order Best. Movie. Year. Ever.: How 1999 Blew Up the Big Screen, by Brian Raftery (Simon & Schuster). On sale: April 16, 2019