Morgan Neville

January 29, 2021

Netflix Awards FYC

A conversation with composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross on behalf of Mank. Moderated by Morgan Neville.

Morgan Neville

January 29, 2021

Netflix Awards FYC

A conversation with composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross on behalf of Mank. Moderated by Morgan Neville.

Mavromates and director David Fincher oversaw a team of four VFX Supervisors to deliver the period film.

Clarence Moye

February 9, 2021

Awards Daily

When tackling a period-centered project like Mank, David Fincher and his assembly of below the line craftspersons create magic, fully immersing the viewer in a faithfully recreated 1930s-era California. While the project leveraged many real-world locations and built sets, changing times and the absence of an unlimited budget posed some challenges to create that immersive world Fincher and team demanded. To complete the illusion, the filmmakers looked to co-producer Peter Mavromates, who led a team of four visual effects (VFX) supervisors.

Now, Mank isn’t effects-heavy The Avengers, but that doesn’t mean VFX aren’t just as critical to the film’s storytelling and overall atmosphere.

“The assumption, at minimum, is that you’re going to at least need to retouch a background to get rid of modern anachronisms,” Mavromates explained. “As in this movie, there are situations where David [Fincher] will want to actually replace the background so that period buildings are back there.”

Glenn Kiser, Director of the Dolby Institute

February 9, 2021

The Dolby Institute

“Mank” has been a personal passion project for David Fincher for several decades now. His own father wrote the script, about the famously self-destructive writer of “Citizen Kane,” and Fincher was determined to make the film feel as authentic as possible. Almost like it was an undiscovered artifact from Hollywood’s “Golden Age,” insisting for years to film it in black & white, 1:33, and in mono. He once again joined forces with his longtime collaborator, sound designer Ren Klyce, to do exactly that. But building this time capsule turned out to be a surprisingly challenging process.

“It’s beyond production value. Sound is a portal into a stranger’s mind that is incredibly influential. And if we don’t avail ourselves of this access, um… then we’re stupid and we should die (laughs).” – David Fincher, director of “Mank”

Listen to the Sound + Image Lab: The Dolby Institute Podcast:

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

Google Podcasts

SoundCloud

Amazon Music

Stitcher

TuneIn

Connect with Dolby on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn. Movie buff? Follow Dolby Cinema on Instagram.

Tom Kenny

February 8th, 2021

Mix Magazine / SoundWorks Collection

Director David Fincher tasked the sound crew with reviving the feel of the Golden Age of Hollywood in the track. They came up with a process of combining old and new technologies to create a “patina” for playback.

Ren Klyce, Sound Designer

Drew Kunin, Production Sound Mixer

Jeremy Molod, Supervising Sound Editor

Nathan Nance, Re-Recording Mixer

Moderated by Tom Kenny, Editor of Mix

Listen to the SoundWorks Collection podcast on:

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

SoundCloud

Stitcher

The Golden Age Sound of ‘Mank’

Jennifer Walden

February 10, 2021

Mix Magazine

Production Designer Don Burt reveals the secrets of the film’s authentic rendering of a bygone Los Angeles

Adam Woodward

February 8, 2021

The Spaces

Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane was made at the height of Hollywood’s so-called Golden Age, a time when studios controlled their stars and super-producers like Louis B Mayer reigned supreme. David Fincher’s Mank, which tells the story of how legendary screenwriter Herman J Mankiewicz wrote one of the greatest films of all time, is a faithful reconstruction of Tinseltown as it appeared in the 1930s and early ’40s.

The unmistakable air of Old Hollywood glamour that infuses every frame of Mank was the result of months of planning and preparation by production designer Don Burt, who has worked on every Fincher release since 2007’s Zodiac.

Burt walks us through the key locations from the film, some of which were scouted by himself while others were created on studio soundstages – just as Welles would have done.

Matt Grobar

February 8, 2021

Deadline

On David Fincher’s Mank, sound designer Ren Klyce was tasked with crafting a monaural soundtrack, similar to those heard in films of the ’30s and ’40s, engaging in a laborious, experimental process, in order to round out the world of one of the year’s most distinctive films.

Scripted by Fincher’s late father Jack, the director’s longtime passion project follows Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman)—a washed up, alcoholic screenwriter from Hollywood’s Golden Age—as he endeavors to finish the screenplay for the iconic Citizen Kane.

The goal with Mank was to immerse viewers in its period world through the creation of visual and sonic ‘patinas,’ each working in concert with the other. While cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt shot the black-and-white film digitally, at extremely high resolution—allowing Fincher to degrade the image in post—Klyce would tinker with sonic degradation, tapping into all of the characteristics that gave early 20th century soundtracks their unique feel.

One of Fincher’s closest collaborators—who has worked with him on 10 features and two television series since 1995—Klyce had experimented only briefly with mono sound in the past, on a handful of Fincher films. “But we never did it with the conviction of, ‘This is the purpose,’” the sound designer notes, “‘because we want it to feel like it was made using the technology of the time.’”

Below, the seven-time Oscar nominee recalls his earliest conversations with Fincher about Mank, and the multifaceted process of fashioning its vintage sonic palette.

Edward Douglas

February 8, 2021

Below the Line

There are many reasons why there’s a general wave of excitement whenever there’s a new David Fincher movie. That’s particularly been the case with Mank considering the six-year gap since Fincher’s last film Gone Girl, roughly half that time in which Fincher was making the series Mindhunter for Netflix.

Most of Fincher’s fans within and outside the industry see the filmmaker as a modern master of the visual medium, and Mank offers further proof of this with stunning shots recreating Hollywood in the ‘30s and ‘40s, fully realized background environments in which well-known icons from the era discuss the political climate of the times, both in the country and in Tinsel Town itself. At the center of it all is Gary Oldman’s Herman Mankiewicz, the illustrious screenwriter who would win a shared Oscar for co-writing Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane.

One person who has been along for the ride watching Fincher’s rise as a visionary filmmaker is Peter Mavromates, whose first film with Fincher was 1997’s The Game, but who first met the director on a Michael Jackson video and a commercial he directed. Mavromates has worked in post for over 35 years, as one of the first to champion the benefits of combining analog film with digital post, producing his first DI (Digital Intermediary) for Fincher’s 2002 movie, Panic Room, which was shot on analog. Five years later, he did the same for Zodiac, Fincher’s first digitally-shot film.

As Fincher’s Post-Production Supervisor, Mavromates’ duties continued to expand and evolve, his duties involving all the budgeting and hiring when it comes to the post process. “I like to describe it as once the image is captured, it becomes my problem,” he told Below the Line over a Zoom call a few weeks back.

Clarence Moye

February 8, 2021

Awards Daily

Netflix’s Mank marks editor Kirk Baxter’s fifth cinematic collaboration with director David Fincher. It’s a collaboration that proved extremely rewarding for the editor who received two Academy Awards for his work with Fincher — 2010’s The Social Network and 2011’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. In fact, Baxter and then co-editor Angus Wall achieved an incredibly rare feat with their Dragon Tattoo win given its lack of a Best Picture nomination.

That successful collaborative history with Fincher stems from Baxter’s willingness to accept feedback and push his work to be the best it can be.

“I don’t seek to be finished, and I remain curious with the material. I don’t work from a defensive standpoint. I don’t have this protectionist quality about the work I’ve done,” Baxter explained when ruminating on his partnership with Fincher. “I just show the work, and if he’s into it, he’s into it. If he’s got a way that he thinks it can be improved, then I’m into that. That’s the relationship. It’s a lot of back and forth, and I’m really comfortable doing it.”

Abe Friedtanzer

February 7, 2021

AwardsWatch

One of the most acclaimed films of all time is Citizen Kane, released in 1941 and starring a young Orson Welles, who also directed. David Fincher’s epic Mank examines the role of another influential player, screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz. Released in select theaters in November before a December debut on Netflix, this black-and-white film is full of eye-popping sets and costumes. I had the chance to speak with production designer Donald Graham Burt and costume designer Trish Summerville about their approach to this ambitious project, their affinity for each other’s processes, and working with frequent collaborator David Fincher.

Abe Friedtanzer: When did you first see Citizen Kane, and how much did you want this film to look like that one?

Donald Graham Burt: Wow. I don’t know when I first saw it. It was years ago. And then of course I looked at it again before this film started. I don’t think it was so much about making it look like Citizen Kane. Obviously, the narrative involves Citizen Kane. It was more about making this be a film that felt like it was made during the same period. It was more about the 30s. We weren’t trying to replicate Citizen Kane in any way, shape, or form. That wasn’t the purpose of it. I don’t think we ever sat down and said, okay, in Citizen Kane, they did this, and they had a set that did this, and costumes that did this. That wasn’t the approach to it. Would you agree, Trish?

Trish Summerville: Definitely. I also, like Don, can’t remember when I first saw it. I was pretty young. I rewatched it, but wasn’t trying to mimic any of the costumes in it. It was just information for us to gather. We also looked at a bunch of other 30s black-and-white films.

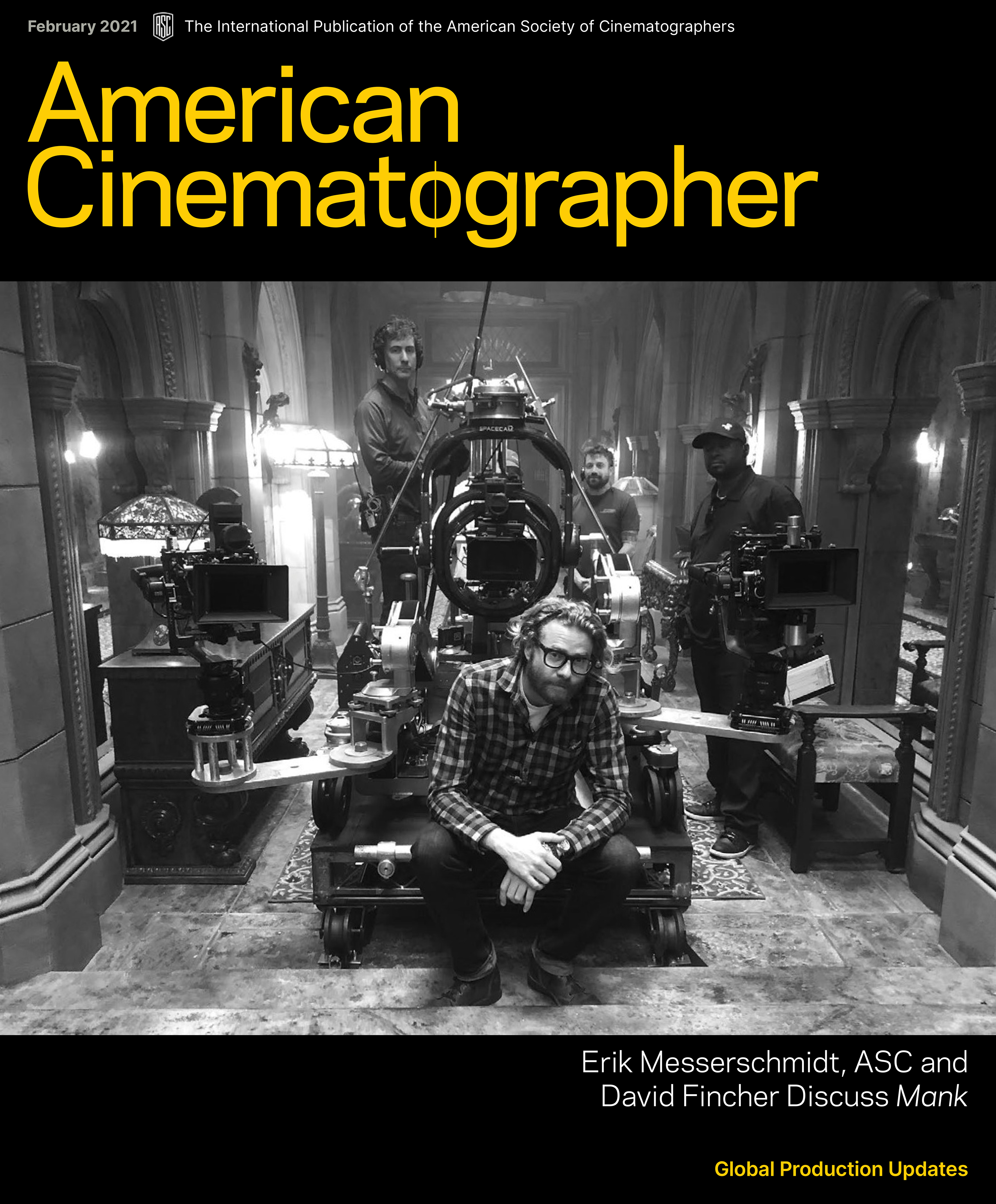

Cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt, ASC and director David Fincher discuss their creative collaboration.

Stephen Pizzello

February 4, 2021

American Cinematographer

Mank frames the origin story of Citizen Kane from the perspective of screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz as he’s hit a low point in life. Alcoholic, world-weary and hobbled by a broken leg sustained in a car crash, Mankiewicz is trundled off to a dusty desert cottage in Victorville, Calif., accompanied by a nurse and a typist tasked with keeping their cantankerous patient off the bottle so he can complete a screenplay for Orson Welles — a script that will serve as the foundation of Kane.

Pressed by Welles to finish the project, the bedridden “Mank” (as he’s known to his friends and colleagues) struggles to find creative inspiration, eventually drawing upon his memories of businessman, newspaper tycoon and politician William Randolph Hearst. Flashbacks transport us back to Mank’s headier days as a handsomely paid Hollywood scripter. After amusing Hearst with his barbed wit on a movie location, Mankiewicz is invited to mingle with members of the mogul’s inner circle and renews a friendship with Hearst’s mistress, actress and comedian Marion Davies. Mank’s Hollywood career is thriving, and his social standing is on the rise, but his proximity to power allows him to observe its corrosive influence firsthand — souring his worldview, but ultimately informing the plot of Citizen Kane and the sardonically unflattering portrait of its Hearst-like protagonist, Charles Foster Kane.

The script for Mank was initially fashioned by director David Fincher’s father, Jack, a journalist and screenwriter, who empathized with Mankiewicz’s plight and leaned into the controversial assertions of film critic Pauline Kael, whose 1971 essay in The New Yorker, “Raising Kane,” maintained that Mankiewicz was almost entirely responsible for the Citizen Kane screenplay, with little input from Welles. (That thesis has since been partially debunked by Welles supporters, including director and former film critic Peter Bogdanovich.)

Following his father’s death in 2003, Fincher retooled the Mank script with the help of screenwriter Eric Roth, making it less antagonistic toward Welles. “I never felt that the film should be a posthumous arbitration — that’s never been of interest to me,” Fincher told AC during a 90-minute Zoom interview that included Mank cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt, ASC. “What was interesting to me was that it’s [essentially] Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead — here’s a guy in the wings, and it’s his experience of this situation. What I found fascinating about Mankiewicz was [that] 30 percent of his output as a professional screenwriter in Hollywood was uncredited. And for one brief, shining moment — on a movie he did when he was old enough to sign a contract and understand the terms expressly — he said, ‘No, no, no — I don’t want this one to get away.’”

Erik Messerschmidt, ASC (foreground) on the set with (background, from left) boom operator Michael Primmer, B-dolly grip Mike Mull and A-camera 2nd assistant Gary Bevans. (Photo by key makeup artist Gigi Williams, courtesy of Netflix.)